Author describes player's transformation

Author describes player's transformationBy Regis Behe

PITTSBURGH TRIBUNE-REVIEW

Tuesday, April 25, 2006

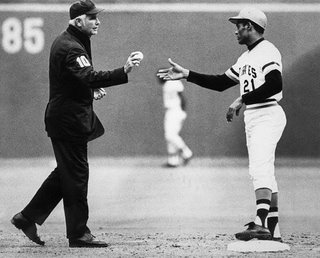

It's a memory that is indelibly etched in the mind of any Pittsburgher who saw a baseball game during 1950s, 1960s or early 1970s.

Roberto Clemente. Striding to home plate, rotating his neck from side to side. Stepping into the batter's box, raising his right hand for time, the bat held aloft in his left hand as he pawed the dirt with his foot. Settling into his stance, the heels of his feet edging up against the white lime, his hands held back, his left leg bent in static energy.

Then, when he got his pitch, the lightning quick reflexes, the resounding crack of wooden bat on leather baseball, a white blur landing in the outfield and sometimes beyond.

Three thousand times during his career, Roberto Clemente lashed baseballs for hits, an extraordinary achievement in a sport in which failure always exceeds achievement. Three-thousand base hits, the stuff of immortality, ensuring enshrinement in baseball's Hall of Fame.

But ultimately, the number 3,000 is insignificant when it comes to describing Roberto Clemente.

He was like football's Gale Sayers or basketball player Julius Erving, says David Maraniss, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of "Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball's Last Hero" (Simon & Schuster, $26), released today.

Those kind of athletes, Maraniss says, "when they were on the field, you couldn't take your eyes off them. They had just idiosyncratic ways, unlike any other players in the way they played the game. ... Statistically, they were winners, but you wouldn't put them as the best. Yet to so many, they were the best. I grew up in Madison, Wis., and he was my guy because of something I couldn't describe, what I guess I call the beautiful fury that he played with."

Clemente still evokes the kind of passion reserved for larger-than-life figures, the John Waynes, John F. Kennedys or John Lennons. The new book makes no case for canonization. Maraniss relates the icon's failures, including his often mercurial relations with the press, a temperamental and inexcusable episode in which he punched a fan in Philadelphia, and, before his marriage, the intimation that he never lacked for the company of attractive women, especially on road trips.

But Maraniss also found that Clemente was the rare athlete who not only did not suffer an erosion of skills as he aged, but one who became a better human being.

"I think he was growing, and I think you see that in the final three years of his life," Maraniss says. "A lot athletes as they grow older sort of diminish and get sour. Clemente started out with a chip on his shoulder, and he grew into a larger figure year by year, over those 18 years (of his career). In the final three or four years, he was talking in English, his second language, of giving motivational speeches about the need to serve others. ... When you see growth like that, particularly in an athlete, that's a real mark of character."

Clemente's stature might have been diminished if not for two crucial episodes in the last years of his life. The first was his amazing performance, at the age of 37, in the 1971 World Series. In the 1960 series, which the Pirates also won, Clemente had performed well, but sat alone in the dressing room after Game 7, apart from his teammates and ignored by the media.

Eleven years later, after batting .414 and being typically superb in the field, he was named the Most Valuable Player. Instead of being forgotten, he was feted by his teammates and reporters, finally earning the respect and adulation he craved.

"It was really the only time he was on the national stage as a ballplayer, aside from all-star games, where he shared the stage with (Hank) Aaron, (Willie) Mays and some of the other greats," Maraniss says. "The Pirates couldn't have won it without (pitcher) Steve Blass. Every Pittsburgh fan knows that. But nonetheless, the whole series was Clemente. It was his stage, and he seized it in an incredible way."

The second episode that contributed to the apotheosis of Clemente also was his final act: The ill-fated of mission of mercy to Nicaragua, which had been struck by an earthquake, on New Year's Eve 1972. On a plane laden with relief supplies, Clemente disappeared off the coast of his native Puerto Rico into the Atlantic Ocean, one item of clothing washed ashore as the only surviving remnant of the man.

"One sock, that's all, the rest to sharks and gods," Maraniss writes.

If he had lived, Clemente's athletic feats still would be appreciated. His early death, and dying as he was attempting to help the less fortunate, took him into another realm.

"He wouldn't be the mythological, saint-like creature that he is because he would still be a human being," Maraniss says. "The nature of his death exponentially enhanced the nature of his life, which was good enough. ... I know the term hero is overused, but it is in my title because it's the classic definition: somebody who dies in the service of others."

Tidbits from the book

The statistics of Roberto Clemente are a matter of record. The late Pirates outfielder, enshrined in the Hall of Fame in 1973, is one of 26 players to collect 3,000 hits, and he earned 12 consecutive Gold Gloves for fielding.

In David Maraniss' new book "Clemente: The Passion of Grace of Baseball's Last Hero," the Pulitzer Prize-winning author looks beyond the numbers to the essence of the athlete who remains a legend in Pittsburgh and his homeland of Puerto Rico. Here are some interesting tidbits from the book:

In David Maraniss' new book "Clemente: The Passion of Grace of Baseball's Last Hero," the Pulitzer Prize-winning author looks beyond the numbers to the essence of the athlete who remains a legend in Pittsburgh and his homeland of Puerto Rico. Here are some interesting tidbits from the book:* Clemente's nickname was Momen, short for "momentito," roughly translated as "give me a second." From an early age, Clemente had a habit of saying momentito when he was interrupted or asked to do something.

* During his career, much was made of Clemente's habit of expounding on his physical problems. Those ailments were not figments of his imagination, but stemmed from wrenching his neck and spine in a car accident in 1954. Aches and pains in these areas would dog him the rest of his career, but Clemente still holds the record for games played in a Pirates uniform, numbering 2,433.

* Clemente was part of the first all-black and Latin lineup in Major League Baseball history. On Sept. 1, 1971, in a game against the Philadelphia Phillies, the Pirates fielded a lineup of Clemente in rightfield, Gene Clines in centerfield, Willie Stargell in leftfield, first basemen Al Oliver, second basemen Rennie Stennett, Jackie Hernandez at shortstop, Dave Cash at third base, catcher Manny Sanguillen and pitcher Doc Ellis.

* Before every game, Clemente took a spoonful of honey to relax.

* Clemente had his greatest success as a hitter using a bat designed for an anonymous player.

After using Stan Musial and Vern Stephens models at the beginning of his career, in 1961 Clemente switched to a U1 model made for Bernard Bartholomew "Frenchy" Uhalt, who played a mere 57 games for the Chicago White Sox in 1934. Uhalt had 40 career hits, but Clemente had his greatest success with the bats, measuring 36 inches long and weighing 34 to 35 ounces.

Another unusual feature of the U1s: They didn't have a knob. Instead, they tapered out at the bottom.

* Clemente's name adorns two hospitals, 40 public schools and more than 200 ball fields in the United States, Puerto Rico and Europe. Japanese baseball gives an award named after Clemente for distinguished community service.

* After Pirates pitcher Bob Veale rubbed Clemente's shoulder before a contest in the mid-1960s, he went on a hitting streak. Every game thereafter, Clemente sought out Veale and his touch. "Where's Bob?" became a common refrain in the Pirates clubhouse.

Fans remember famous outfielder

PNC Park usher Tony DelVecchiohas seen all the baseball greats from Pie Traynor to Willie Stargell.

As a kid, collecting soda bottles in metal buckets at Forbes Field, DelVecchio saw Babe Ruth hit his last three home runs. He remembers when a Pirates bench coach named Honus Wagner hit ground balls on hot days for infield practice.

Even after 68 years as a Pirates usher, there's still one player who stands above the rest. Mention Roberto Clemente, and the 86-year-old DelVecchio gives you a nod and that knowing look.

"Ah yeah, he was the best all-around," DelVecchio says from his current assignment in the right-center field seats at PNC Park. "Clemente had an arm, a golden arm. When he threw the ball from right field, it landed in the third baseman's glove. It never hit the ground.

"Man, he could go after a ball."

Many more memories of Clemente are expected to surround the publication of a new book by David Maraniss titled "Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball's Last Hero."

DelVecchio wasn't the only one impressed forever by Clemente, who died on New Year's Eve 1972. He was killed in a plane crash while attempting to deliver food and medical supplies to Nicaragua after an earthquake.

Irene DeLong, 83, Munhall

"I've been watching the Pirates since 1948, and I'll never forget the time I saw Clemente throw a ball all the way to home without it hitting the ground. Dave Parker could really throw the ball, too, but not like Clemente."

Don Soldano, 68, Lawrenceville

"If you remember the first-base line at Forbes Field, the box seats stuck out, and then it went back to the wall where you could lose track of a ball. I remember Clemente running into that cutoff where you couldn't see him. He caught the ball back there and threw a peg to home plate. It was a perfect strike to, I think it was, (catcher Jim) Pagliaroni, and he got the runner out at home plate."

Al Rowe, 76, Jefferson Hills

"Clemente used to get those hits between the outfielders -- those betweeners before there was artificial turf -- and he'd go for triples. And he used to throw out runners trying to go from first to third on a single. When the umpire called him out, the runner would just look out at right field. How could it happen? Boy, he threw a lot of runners out."

Manny Sanguillen, former Pirates catcher

"I never saw a better ball player than Roberto Clemente in my life. He was a special person and my close brother. You see the players now, and nobody gets close to him. Maybe they hit more home runs, but they're using things that he never used."

Al Sid, Stubenville, Ohio

"Clemente was terrific. He was a great man, and it was a great loss when he died, because he contributed so much all the way around."

Regis Behe can be reached at rbehe@tribweb.com or (412)320-7990.