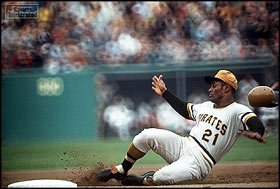

Roberto Clemente: Unappreciated during his career, he was one of baseball's greatest.

Dec. 20, 2005. 01:00 AM

The Toronto Star

Appeared Jan. 2, 1973

TORONTO—This time, there can be no doubting the seriousness of Roberto Clemente's injuries. Roberto Clemente, one of the most talented baseball players of his time — and, until recent years, one of the most unappreciated of superstars — is dead.

TORONTO—This time, there can be no doubting the seriousness of Roberto Clemente's injuries. Roberto Clemente, one of the most talented baseball players of his time — and, until recent years, one of the most unappreciated of superstars — is dead.Clemente, who spent most of his 18 years as a big leaguer defending himself against insinuations that he was a hypochondriac — that he was the type of athlete who would apply a cast to a hangnail — lost his life on a mission of mercy.

He could have been enjoying the festive season at his elaborate home near San Juan. Had he wished, he could have been picking up easy money in the Caribbean winter league. He could have been fishing or playing golf.

Clemente had given his name to the organization which was appealing for aid to the victims of the earthquake in Nicaragua. That would have been enough to guarantee its success in Puerto Rico, where he was a household idol.

He was anxious to do more than that. Throughout the holiday season, he participated in television and radio appeals for relief supplies and money. When the mercy flight was ready, he insisted on seeing the job through. The plane had gone only a short distance before it crashed into the sea.

Thus, fate provided a grimly fitting chapter to the career of an athlete whose aches and pains, injuries and disabilities had been ridiculed by scoffers who couldn't carry his shoelaces, practically from the day he joined the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1955. The stature of the man is clear, at last.

Clemente supplied them with ammunition by worrying out loud about his physical condition. He always was afraid that he wouldn't be able to play up to his potential.

Clemente supplied them with ammunition by worrying out loud about his physical condition. He always was afraid that he wouldn't be able to play up to his potential.The last time big league fans were destined to see him was that autumn day at Cincinnati when Bob Moose came out of the Pittsburgh bullpen to make a wild pitch that ended a tight five-game series and established the Reds as champions of the National League.

The Pittsburgh hitting had dried up in areas where it was supposed to be most productive and damaging — Clemente, Willie Stargell, Richie Hebner — and Clemente's head-wagging contortions became more vigorous with each appearance at the plate.

He believed the shoulder-shrugging and head-bobbing relaxed his muscles. They may have had a psychological value, too. Rival pitchers had to be aware that he was a dangerous money hitter — who batted .414 in the World Series of 1971.

There was little optimism in the Pittsburgh clubhouse after that game. The Pirates firmly believed they were a better team than the Reds — better than any other team in the world.

"There will be another time," Clemente consoled himself. "Yes, I will be back if I feel good."

Clemente seldom confessed to feeling fine. In 1956, the year after the Pirates stole him from the Dodgers for the $4,000 draft fee, Clemente was hitting .335 when he was certain that something in his elbow had popped.

The following season, he had the miseries in his back. Doctors despaired of finding the cause. They finally separated him from his tonsils. Roberto hired two chiropractors, during the off-season, to work on his back.

The injury which provided the most material for cracks about Clemente's fragility occurred in December of 1964. Roberto was using a new power mower to manicure his lawn in Puerto Rico.

The mower churned up a rock which hit him on the hip. By this time he was one of baseball's top hitters. That he should be bruised by a pitch thrown by a lawnmower was good for much witty prose.

It wasn't so funny — especially for the Pirates — when he collapsed en route to first base after pinch-hitting in the Puerto Rican all-star game. Why was he playing baseball when he had a stone bruise on his hip? Well, the folks down there asked him to help them at the box office. He obliged.

The leg injury and subsequent complications were much more serious than even the Pittsburgh club had suspected. He finally had to undergo surgery to relieve pressure caused by internal bleeding.

The leg injury and subsequent complications were much more serious than even the Pittsburgh club had suspected. He finally had to undergo surgery to relieve pressure caused by internal bleeding.Then he caught malarial fever. Doctors said that probably came from his hog farm. All the Pirates knew was that he had to miss the early part of training camp.

When the season was over, they had to admit it hadn't been such a calamity, after all. Clemente appeared in 152 games. He batted .329 to retain his league title. Another significant figure: he walked 43 times.

For a good hitter Clemente usually received few walks. He blamed this correctly on his impatience. When he got to the plate there was one thing on his mind — hit the ball.

Although he prided himself on being a team player, Clemente, on occasion, refuted the very principle which he proclaimed. After the 1960 World Series, which turned Pittsburgh into a madhouse of joy, Clemente took off for San Juan. He bypassed the various clambakes at which the village heroes were applauded.

Clemente's feelings had been hurt because he felt his feat of hitting safely in every game had been withheld from public attention by the sportswriters, for whom he had something less than brotherly love.

His relationship with them was not improved when the baseball writers named Dick Groat, of his own club, as the league's most valuable player. Clemente felt it was an honour which he had earned.

Recognition, strangely enough, was something which seemed to shun him. His first contract as a ball player came because he played softball in a city league. One of the softball players tipped off the owner of a local baseball team that a prospect was in their midst.

Later, when the Dodgers had him stashed away at Montreal, where he was used sparingly, a Pittsburgh scout, Clyde Sukeforth, happened to spot him while he was on a mission to watch a pitcher — Joe Black.

The most frustrating incident occurred in the 1961 all-star game at Candlestick Park. Clemente hit a triple, a sacrifice fly and a single that drove in the winning run in the 10th. Next day, all the columnists wrote about the gale that blew pitcher Stu Miller off the mound.

Even Clemente would have to agree that the final assessments of his career have been factual. He has been described as one of the greatest ball players of all time — a statement of fact.

No comments:

Post a Comment