February 6, 2006

February 6, 2006DREW SHARP

FREE PRESS COLUMNIST

A son's patience, forged from a mother's dogged determination, found its reward Sunday in a spotlight that nobody seemed to want.

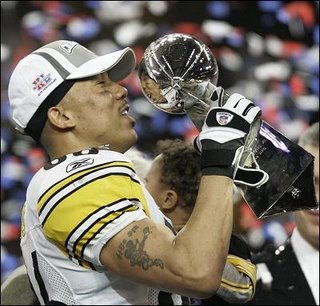

Super Bowl XL inevitably found its star, but when it did, he didn't want to take the bow alone. Hines Ward wanted to share the moment with Jerome Bettis, Pittsburgh's aging warrior who inspired the Steelers' run to the world championship.

"This is for you, Bus," Ward told him as the cameras converged when time and Bettis' Hall of Fame career expired. "I love you, man."

Ward earned Most Valuable Player honors for a game that was super in name only. There was too much sloppiness, perhaps indicative of the moment swallowing the man. Too many guys left too many plays on the field, but Ward did just enough at the right time to stand out.

Ward's fourth-quarter touchdown off a gadget reverse pass delivered the fatal dagger to Seattle, the first wound to the Seahawks that wasn't self-inflicted.

But Ward deserves the award more because he best personifies the Steelers' code: If you believe, you can achieve.

They're not afraid to wait. They're not afraid to work. The fingerprints of their endurance were all over the Steelers' 21-10 victory at Ford Field.

Running back Willie Parker rewrote the Super Bowl records with a 75-yard touchdown gallop barely one minute into the second half. He went undrafted after starting only five games in four years at North Carolina.

But he never gave up.

Bill Cowher has the longest tenure of current NFL head coaches -- 14 years and counting -- but until Sunday he was remembered more for the conference championship games he had lost on his home turf.

Still, he persevered.

And Ward was considered too small to play quarterback, too slow to play running back and too fragile to endure the punishment of coming across the middle as a wide receiver at this level.

Only the Steelers saw that he was determined to prove his doubters wrong.

"When you think of Pittsburgh receivers," Ward said. "You naturally think of (Lynn) Swann and (John) Stallworth. It's flattering being compared to those guys, but I've never felt that I belonged in that group. Winning a Super Bowl solidifies my career. It's a great honor (winning the MVP), but I'm not here without so many other people, and I can't forget that."

Ward dedicated the performance to his mother, Kim Young-hee, a South Korean native. She married an American soldier and moved to the United States, but Ward's parents soon divorced. She initially got custody of her son, but her inability to grasp the English language and American culture hindered her employment opportunities.

She couldn't support her son, and a court stripped her of custodial rights. Ward lived with his father, who had remarried, but the special connection with his mother never dissipated. At age 8, Ward ran away from home and reunited with his mother in Atlanta.

"She could have quit and given up, but she didn't," said Ward. "She taught me the greatest lesson imaginable. Keep working and keep fighting, and you're going to find your way."

Ward played three positions at Georgia -- quarterback, running back and wide receiver. He'd do anything to get on the field because his mother taught him that sometimes, that's necessary.

That's what makes this championship special. It was old school.

The Steelers are one of the last family-owned franchises. Team president Dan Rooney began with the club as water boy after begging his father, Art Sr., for any role on the team. He was 11 at the time.

He likes that same attitude in his players.

The Steelers are an anomaly, a model of consistency in an era of free agency that promotes impatience. They've boasted the best record in the NFL in the 13 years of the salary cap, and that's because they believe in people more than records, more than wins and losses.

Cowher probably would have been fired elsewhere, after suffering through three consecutive non-playoff seasons at the turn of the millennium, but the Steelers don't have a reflexive management style. Cowher twice offered his resignation, but each time Rooney conveyed his confidence that the organization's patience would be rewarded.

The Steelers trust their plan. They trust their people. And they trust that time will vindicate them.

Ward knows he might not have gotten this opportunity with any other team. When the Steelers drafted him in the third round in 1998, they weren't exactly sure where Ward would fit.

"We just thought that he was a football player," said Cowher. "He had a great work ethic and that enabled him to find his role."

The moral of this championship is that time isn't necessarily the villain.

Contact DREW SHARP at 313-223-4055 or dsharp@freepress.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment