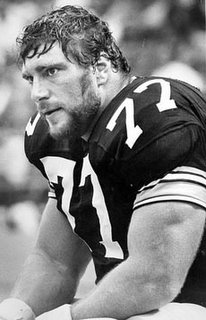

Steve Courson

Steve CoursonBy The Los Angeles Times

Tuesday, July 18, 2006

One was lifting weights at home. Another was training for a triathlon. A third was watching a game at a friend's house.

Regular guys doing regular things.

Then there were the others.

One drank antifreeze. Another was in a high-speed chase.

Two things in common among all:

They were Pittsburgh Steelers; and they died in the last six years.

Fresh off their first Super Bowl victory in 26 years, the Steelers have experienced the emotional gamut. The franchise has lost 18 former players -- age 35 to 58 -- since 2000, including seven in the last 16 months.

"There is no explanation," said Joe Gordon, a Steelers executive from 1969 through '98. "We just shake our heads and ask why."

The numbers are startling. Of the NFL players from the 1970s and '80s who have died since 2000, more than one in five -- 16 of 77 -- were Steelers.

"It's just an anomaly that we can't explain," said John Stallworth, who starred at receiver for Steelers teams from 1974 to 1987. "From an emotional standpoint it just makes you sad and makes you feel like the time we spent together was even more precious."

Freak accidents led to some of the deaths, and at least one was a suicide. Others share hauntingly familiar details.

Seven died of heart failure: Jim Clack, 58; Ray Oldham, 54; Dave Brown, 52; Mike Webster, 50; Steve Furness, 49; Joe Gilliam, 49; and Tyrone McGriff, 41. (In 1996, four years before the steady succession of Steelers deaths, longtime center Ray Mansfield died of a heart attack at 55.)

There is speculation that steroid abuse could have played a role in some of the deaths, but no hard evidence. It's just as plausible that weight issues were a factor. Counting Mansfield, five of the eight heart-attack victims played on the offensive or defensive line.

The circumstances surrounding some of the other deaths were unusual:

* Steve Courson, 50, was killed outside his Farmington, Pa., home in November while trying to remove a 44-foot tree from his property. The former guard was crushed while apparently trying to save his dog, after a gust of wind changed the direction of the falling tree. His black Labrador retriever was found alive, tangled in Courson's legs.

* In March 2005, David Little was bench-pressing weights alone at his Miami home when the coroner determined he suffered a heart arrhythmia, causing the 46-year-old former linebacker to drop a 250-pound barbell on his chest. The bar rolled across his neck and suffocated him.

* Terry Long, 45, an offensive guard whose eight-year career was derailed by a positive test for steroids, committed suicide in Pittsburgh in June 2005 by drinking antifreeze. Twice divorced, he had serious legal problems stemming from his failed food-processing business and had made two previous suicide attempts.

The youngest of the Steelers to die was 36-year-old Justin Strzelczyk, a tackle who had a series of run-ins with the law after he retired. He died after a 40-mile, high-speed chase on the New York Thruway in September 2004. Driving his Ford F-250 pickup at speeds in excess of 100 mph, Strzelczyk made obscene gestures and tossed beer bottles at the police following him. The chase came to a fiery end when, while on the wrong side of the road, he slammed into a tanker truck. The string of deaths -- most recently that of receiver Theo Bell, who died June 21 of kidney disease and the skin ailment scleroderma -- have reverberated through the Steelers, the city of Pittsburgh and beyond.

"Just the fact that the Steelers are such an integral part of this community -- probably more so than most NFL cities -- it obviously hits home for a lot of people," Gordon said. "It's hard to accept."

Men who won a combined 20 Super Bowl rings, the deceased Steelers were part of one of the most hallowed organizations in sports. "When I was young I convinced myself that I was going to do something with my life so that my death wouldn't be the end of me," Stallworth said. "In the lives of these men, they were a part of something special. People in Pittsburgh and around the country will remember them for that."

Some were as much pioneers as players. Gilliam was among the NFL's first black quarterbacks. He started for Pittsburgh in 1974 before Terry Bradshaw reclaimed the job.

When Gilliam's career ended, his life took a downward turn. He struggled with addictions to cocaine and heroin, and sometimes was homeless. In 1995, he was discovered sleeping in a cardboard box under a bridge in Nashville.

But his life was on an upswing just before his death. Saying he was drug free, he lectured children on the perils of drug abuse. In 2000, on Christmas Day, he died while watching a football game at a friend's house.

Of the 22 players who were part of all four Pittsburgh Super Bowl teams of the 1970s, Webster was the last to retire and, after Furness, the second to die.

An All-Pro center who played in a franchise-record 220 games, "Iron Mike" was known for playing bare-armed no matter how cold the conditions, and for dominating larger defenders. He paid a price, however. Doctors said the battering he had taken damaged the frontal lobe of his brain, affecting his attention span and concentration. That likely contributed to the many setbacks he endured after his career, among them a failed marriage, a string of bad investments, and occasional homelessness.

Also after his career, he admitted he tried anabolic steroids as a player, but maintained they were not responsible for his condition. He died of a heart attack in September 2002.

"Webby was my hero," longtime Steelers tackle Tunch Ilkin said. "That broke my heart. I'd seen what was going on with his life at the end."

For years, the Steelers have been dogged by rumors that several of them used performance-enhancing drugs in the 1970s. In an interview last year, Jim Haslett, then coach of the New Orleans Saints, admitted to experimenting with steroids as a Buffalo linebacker, and said the use of those drugs among NFL players started with the Steelers. The NFL didn't begin testing for steroids until 1987, becoming the first professional sports league to do so.

Although Haslett didn't deny making those comments, he later apologized to Steelers owner Dan Rooney, who called the accusation "totally false." Former Pittsburgh receiver Lynn Swann agreed with Rooney, saying he was "very surprised" by Haslett's claim.

"He's misinformed," Swann said. "He was not a part of that team. I was on that team, and I don't use steroids. And I couldn't tell you of who was on that team if anybody used steroids.

Pittsburgh the epicenter of steroid use in the NFL? No. I find that very difficult to believe."

However, Peter Furness told the Providence Journal last year that he suspects his brother, Steve, who played defensive tackle for the Steelers from 1972 through '81, used steroids. Steve Furness died in 2000.

In a 1985 interview with Sports Illustrated, Courson became the first NFL player to speak on the record about his steroid use. During his playing days, he had 20-inch biceps and could bench press 600 pounds. He later said that contributed to a life-threatening condition that weakened his heart muscles -- though he also pointed to his hard-living lifestyle as a factor.

For years, Courson was Mr. Steeler. He played in Pittsburgh from 1977 through '83, when he was part of two championship teams. In the last few years of his life, however, he stopped wearing his Super Bowl rings and contemplated starting over in the mountains of Colorado. He felt betrayed, his girlfriend said, by his teammates' refusal to come clean about their steroid use.

"He wanted them to come out and be straight, seeing as it wasn't illegal back then," said Denise Masciola, who dated Courson the last few years of his life. "None of them would. They thought it would hamper their reputation. He felt like they left him just hanging."

Former Pittsburgh safety Donnie Shell, now director of player development for the Carolina Panthers, had hoped Courson would work with Carolina players last fall. A few months earlier, the former teammates had discussed getting together.

"Then I saw it come across the crawl that Steve Courson is dead," Shell said. "You don't know why until you hear the results of the news. Sometimes it's just shocking to hear."

Shell, like Gordon, sees no rhyme nor reason to the deaths. Only a relentless drumbeat of tragedies -- and a reminder that life can be too short.

"There's nothing you can do," he said, "except pray for the families, cherish the memories that you had with them -- they're good memories -- and move on."

No comments:

Post a Comment