Sunday, July 29, 2007

By Rick Shrum, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

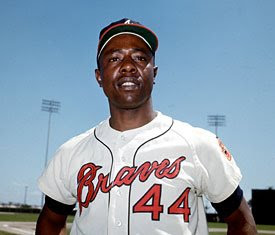

Hank Aaron, right, crosses the plate at Three Rivers Stadium in 1971 after hitting home run No. 598 off Bob Moose April 20, 1971. Catching for the Pirates is Manny Sanguillen.

Click photo for larger image.

Steve Blass was 22, a right-hander on the right track in 1964. He was a Pirates rookie, and his initial appearance was against the Milwaukee Braves and the guy who was tops in his Topps baseball card collection.

Talk about ratcheting up the anxiety.

"I thought, 'Here's Henry Aaron. Do I have his bubble gum card in my pocket?' "

Blass' discomfort hadn't been alleviated by a conversation he'd had with his roommate, Bob Friend, a savvy and respected veteran.

"I asked him, 'How do you pitch against Henry?' " Blass recalled. "He said, 'As infrequently as possible.' "

Now a Pirates broadcaster, Blass said he believes he did not allow a run in his first five innings that day, but cannot recall how he fared in his first faceoff with Hammerin' Hank.

"I've probably blotted it out because I was terrified," he said.

Overall, Blass said he did "fairly well" against Aaron, a right-handed hitter. "Five homers in 10 years, and I faced the Braves a lot."

The roomie? In nearly a decade as well, Hank yanked 12 out of the yard against him.

As Barry Bonds' inexorable pursuit of Aaron's major-league home run record continues -- he has 753, two shy of tying -- a number of former Pirates players recounted playing against The Hammer.

They remember those quick wrists, lethal hands and swift feet. Oh, and the body -- 6 feet, 180 pounds -- that was shaped by Mother Nature, not science.

The birth of a legend

Aaron is 73 now and a Braves employee for 54 of the past 56 years. He has been the senior vice president since 1989. All season, he has been more like a silent partner, refusing all interview requests during Bonds' quest for 756.

His talents were discernible at a young age. Aaron was 18, out of baseball-rich Mobile, Ala., when he became the star of the semipro Mobile Black Bears in 1951. He was a quick, agile shortstop who, despite batting cross-handed, was recognized as a wondrous hitter.

By season's end, he was offered a contract by the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro Leagues.

The Negro Leagues, at that juncture, were struggling on the field and at the turnstiles -- they were losing quality players to Major League baseball, now that the so-called color barrier had been breached. But this was a better opportunity, so Aaron signed.

The following June, he left the Clowns for the big top, accepting a contract offer from the Boston Braves over one from the New York Giants. The Clowns, interested in solvency, readily agreed to a deal in which the Braves would pay them $2,500 immediately and $7,500 additionally if Aaron stayed with the organization for 30 days.

He did for the next 23 years, first in the minors, then with the Braves in Milwaukee (1954-65) and Atlanta (1966-74).

On April 8 of that 23rd season, 1974, against Dodgers left-hander Al Downing, Aaron launched his 715th home run. He was 40 when he eclipsed the most sacred record in sports, Babe Ruth's 714.

Aaron was traded to the Brewers, then in the American League, during the offseason and completed his career where it started, in Milwaukee, in October 1976. He joined the Braves front office immediately afterward.

His cumulative credentials are impeccable: .305 batting average; 3,771 hits; 2,297 RBIs and 6,856 total bases, both big-league records; 240 stolen bases; and a mere 60 strikeouts per year on the average.

The home run, however, will endure as his trademark.

Thank heaven for Forbes Field

Pirates fans 45 and over may consider this an egregious statistical shortfall, but Aaron smote "only" 78 -- 10.3 percent -- of his homers against their team. That is tied with the Giants for fifth-most victimized staff, behind the Reds (97), Dodgers (95), Cardinals (91) and Cubs (87).

That total is partly attributable to the Pirates playing at cavernous Forbes Field during the majority of Aaron's National League tenure. Still, he launched 31 at Forbes Field in 161/2 seasons.

He homered against Pirates pitchers 22 times each at the Braves' launching pads, County Stadium in Milwaukee and Atlanta's Fulton County Stadium. Aaron homered just three times in 4 1/2 seasons at Three Rivers Stadium.

Aaron, it seemed, had a friend in Friend, bashing 12 off him -- more than any Pirates pitcher.

"His home runs would sometimes get out of the park quickly," Friend said, chuckling, at his Fox Chapel home.

"I remember that I first saw him at Jacksonville in spring training. He didn't have a name -- Who is this Henry Aaron? Well, he hit three doubles and a couple of home runs."

As with Willie Mays, a contemporary and fellow basher, Aaron was known for his power to all fields. His trademark was the line-drive homer.

"I remember how quickly Henry's hands went through the ball," Friend said. "You thought you made a good pitch and he could rifle it any place, down the right-field line, left ..."

Former Pirates right-hander Vernon Law, who lives in Provo, Utah, said: "It was tough to pitch against Willie and Henry because they went with the pitch and used the entire field."

Dick Groat said that wasn't always the case with Aaron. Groat was an outstanding defensive shortstop for the Pirates partly because he scrutinized opposing batters. He said that Aaron eventually became more of a pull hitter.

"He was absolutely impossible to play his first couple of years," said Groat, an Edgewood resident. "He hit the ball like [Roberto] Clemente, from line to line. He was the only hitter in the National League who drove me crazy.

"I guess a couple of years later, he wanted to be more of a pull hitter and he was easier to play. But he could still spray and hit .330."

Groat said it didn't happen

Bob Prince, longtime Pirates broadcaster and renowned storyteller, loved to describe Aaron's hitting style with this oft-told tale:

One afternoon, Aaron lashed a shot toward Groat. The Pirates' shortstop leaped, but the ball grazed his glove ... and continued upward, over left fielder Bob Skinner and the Forbes Field wall.

"Not true," Groat said. "It did not touch my glove."

It was close, though.

"I thought I was going to catch it and Skins knew he was going to catch it," Groat said.

"I timed my leap perfectly. I didn't miss it. Well, it ended up in the light standard.

"This really happened because I remember talking with Skins as we left the field when the inning was over."

Blass may have been comparatively successful against Aaron, but was always wary of The Hammer playing laser tag with him.

"Henry hit line drives," said Blass, of Upper St. Clair. "When you got a scouting report on him, it was hope for the best and hope he doesn't kill one of your infielders.

"Sometimes, you could get him [out pitching] outside. But did you want to pitch him outside and risk dying, or pitch him inside and risk having it sent to the Carnegie Museum?"

Law said, "Aaron had a little weakness in his swing. If you kept the ball down, you had a better chance of getting him out."

But not necessarily a great chance. Law, an accomplished right-hander, the 1960 National League Cy Young recipient, yielded nine homers to Aaron, second among Pirates pitchers.

The inevitable comparison

The current home run king and his imminent successor have had little in common other than their quests and being African-American.

Bonds drives them high and far from the left side, direct contrasts with Aaron. Bonds has the single-season record of 73 homers, has crashed 40 or more eight times, has a .299 career average, and has been the unquestioned star of his day.

He was born in privilege, the son of a former major-leaguer, Bobby. Bonds is generally regarded as brooding, surly and abrasive.

Oh, and at 6-1, 228 pounds, he is a mammoth compared with his formative years with the Pirates (1986-92).

Aaron came from a working-class family and was overshadowed in the 1950s and '60s by the more-flamboyant Mays and the Yankees' Mickey Mantle. Some considered Aaron on a par with Clemente.

Modest in build and temperament, a gentleman by consensus, Aaron was a paragon of consistency in an era when pitching ruled. He never struck more than 45 home runs in a season, yet from 1955-73, he never hit fewer than 24. Aaron topped .300 14 times.

There is a similarity between these two. Each has spent his baseball dotage under a roiling, ominous cloud.

Aaron's was a cloud of racism. The closer he got to Ruth, the more hate mail he received.

Things were so bad heading into the 1974 season, when he was one shy of Ruth, that Aaron was assigned a bodyguard.

Steroid allegations have swirled about Bonds for years. Nothing has been proven, yet the BALCO investigation and Bonds' dramatic change in upper body have fueled speculation that he has been a frequent user.

"If he's taking this stuff, it's a shame because he didn't need it," Friend said. "He's a great athlete and a great ballplayer. He didn't have to take it to get to the Hall of Fame."

Blass said if Bonds, as widely suspected, did take performance-enhancing substances, they did not make him a more effective hitter.

"Steroids make you hit the ball farther, not better," Blass said. "You have to respect Barry Bonds for his abilities. I think he will go down as one of the 20 best ballplayers ever.

"But if people ask if I root for Bonds to break the record, I say 'no.' I have a special place in my heart for Henry because I competed against him."

Rick Shrum can be reached at rshrum@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1911.

No comments:

Post a Comment