Sunday, October 07, 2007

Sunday, October 07, 2007By Robert Dvorchak, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

With the right to the first overall choice in the 1970 draft riding on a coin flip, Dan Rooney deferred to Chicago's Ed McCaskey to make the call while NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle readied his thumb beneath a 1921 silver dollar.

The Bears called heads. The coin spun about a foot in the air and thunked down on a table in a New Orleans hotel. Lady Liberty's image was face down. The eagle side was up. The Steelers had won the toss between the two worst teams in football.

So hardened to losing was the city that the Post-Gazette headline to the top story in the sports section was: "Honest to Goodness -- Steelers Win."

In hindsight, winning the toss was an omen. By the end of the decade, the headlines spoke of triumph after triumph. The team with the NFL's all-time inferiority complex developed a sterling silver swagger. And a city once described as hell with the lid taken off turned into the City of Champions.

Alchemy should work so well.

The franchise that had seen such quarterbacks as Sid Luckman, Johnny Unitas, Len Dawson and Bill Nelsen get away used the first pick to select Terry Bradshaw, a rifle-armed, fleet-of-foot bundle of raw energy who endured a rocky start to become an integral part of the glory days.

Terry Bradshaw and Chuck Noll

A new wind was blowing other ways as well. The Steelers moved into Three Rivers Stadium, and a scratchy-voiced showman named Myron Cope, with his impeccable sense of timing, joined the broadcast team.

"If that stadium had never been built, we'd never have won," Steelers founder Art Rooney once said. "We had second-class facilities in the old days, and we were a second-class team. We went to being a first-class club."

Only a handful of veterans made the transition from old Forbes Field and Pitt Stadium to the new multi-purpose facility and a new start in the American Football Conference, but they noticed a new attitude in the new players coming aboard.

"I don't think they know about the old losing image. They didn't know the Steelers are supposed to lose," lineman Ray Mansfield said at the time. "When I first came to Pittsburgh, even if we won a few games, there was always an expectation of doom."

Still, the bandwagon had plenty of room as the climb started.

Oh, those draft picks

Lynn Swann, Super Bowl X MVP

Lynn Swann, Super Bowl X MVPFor an outfit notorious for botching the draft, the Steelers set a standard that was the envy of the NFL. Chuck Noll believed in molding young talent by building through the draft. Art Rooney Jr., son of the founder, was in charge of personnel with super scout Dick Haley,

Joe Greene was already on board, and Mel Blount arrived in the Bradshaw draft. Jack Ham was added in 1971. The coach preferred Robert Newhouse as a running back in 1972, but the scouts sold him on Franco Harris. Then came the mother lode in 1974 -- Lynn Swann, Jack Lambert, John Stallworth and Mike Webster before the fifth round was over. There was no other draft like it before or since.

But in addition to all those future Hall of Famers, the Steelers scored big in lower rounds, especially with players from traditionally black schools. Credit went to a new talent evaluator, Bill Nunn Sr., who as sports editor of The Pittsburgh Courier had named an annual All-Star team of players from black schools.

Mike Webster

Mike WebsterHe recommended draft choices and free agents such as L.C. Greenwood, Ernie Holmes, Joe Gilliam and Donnie Shell.

By the end of the decade, not a single player on the Super Bowl roster had ever worn another team's uniform. They were all home-grown. A total of 22 players were measured for all four Super Bowl rings.

In a sporting sort of way, Steelers history has a biblical quality. The first 40 years of wandering through the wilderness is the football version of the Old Testament. The new age dawned with a play known by a religious name and interpreted as an act of providence.

'Dee-fence! Dee-fence'

But before the Steelers ascended to the ranks of winners, they had to vanquish the Browns. Cleveland had won 34 of the first 45 games played against the Steelers, and the radio stations in a city where the river caught fire looked down their noses at Pittsburgh.

The breakthrough came on a gray, gloomy Sunday in 1972, with the teams tied for first place, in a game The Pittsburgh Press called Armageddon. It was a chance to right everything for all the bad years, and a resolute bunch of blue-collar fans packed Three Rivers Stadium to be part of it.

The breakthrough came on a gray, gloomy Sunday in 1972, with the teams tied for first place, in a game The Pittsburgh Press called Armageddon. It was a chance to right everything for all the bad years, and a resolute bunch of blue-collar fans packed Three Rivers Stadium to be part of it.A throaty roar went up an hour before the game and never let up. Those who were there on that Dec. 3 game to witness a 30-0 victory can attest that the reinforced concrete actually pulsated as primal voices, without prompting, chanted "Dee-fence! Dee-fence! Dee-fence!" while savoring every delicious moment.

"I got the feeling that if we didn't win, the fans were going to come out of the stands and win it for us," said linebacker Andy Russell, who intercepted a pass and recovered a fumble, leading to 10 points.

From that day on, the Steelers have never failed to sell out a game.

After finishing first in the division for the Steelers' first title of any kind, the Oakland Raiders came to town for the first playoff game here in a quarter century. It was as fun to watch as a street fight. The Steelers allowed their first touchdown in December and fell behind late in the game.

On fourth down, with time nearing expiration, Art Rooney got into the elevator on his way to consoling his team. Then a 17-second sequence buried the Same Old Steelers for good.

A pass thrown to Frenchy Fuqua, who was belted by Jack Tatum the instant the ball arrived, caromed backward end over end. Franco Harris picked it out of the air at shoe-top level at the 42-yard line and ran into the end zone with five seconds left.

In the bedlam, referee Fred Swearingen phoned the press box to confer with Art McNally, the NFL's director of officiating. "You have to call what you saw," the referee was told.

Since none of the officials saw anything to negate the result, Mr. Swearingen raised his arms to signal a winning score, making official the single most electrifying play in NFL history. The fact that the collision and the reception maintain an element of controversy only adds to the mystique.

There was no Super Bowl trophy that year, but the play lives on. Two figures greet passengers headed to baggage claim at the Pittsburgh airport. One is of a young George Washington, who fought to claim the fort that became Pittsburgh. The other is of Franco Harris reaching out to recreate the city's moment of unabashed joy -- the Immaculate Reception.

Darwinism of a sort has a niche in Steelers history because Steelermania evolved from a primate. Well, actually, it evolved from a guy wearing a gorilla suit -- Bob Bubanic of Port Vue, who introduced the world to Gerela's Gorillas, a fan club dedicated to a soccer-style kicker claimed off waivers for $100 in 1971.

Darwinism of a sort has a niche in Steelers history because Steelermania evolved from a primate. Well, actually, it evolved from a guy wearing a gorilla suit -- Bob Bubanic of Port Vue, who introduced the world to Gerela's Gorillas, a fan club dedicated to a soccer-style kicker claimed off waivers for $100 in 1971.He and his pals first rented the monkey suit for $60 a game, then held a raffle to buy it outright for $250. They showed up every Sunday to cheer Roy Gerela and to jinx opposing kickers.

"Yes, I felt like I was part of the team and that. We all did," said Mr. Bubanic. "It was a lot of fun."

All kinds of fans went ape over the Steelers.

Thaddeus Majzer, also from Port Vue, saw Hall of Fame potential in a new linebacker. Beginning in 1971, he hung a sign that said Dobre Shunka, which means Good Ham in Slovak.

Jack Ham

Jack HamAs he watched Jack Ham and the Steelers grow into a team without peer, Mr. Majzer would remind his friends: "Enjoy this while it lasts. You'll never see another football team this good."

In 1972, Tony Stagno and Al Vento brought forth Franco's Italian Army and the battle cry "Run, Paisano, Run!" Their ranks were later graced with the enlistment of Ol' Blue Eyes himself, Frank Sinatra.

Frenchy's Foreign Legion honored running back John Fuqua, whose sartorial splendor included purple suits and platform shoes displaying live goldfish. Ernie Holmes, part of the Steel Curtain front four that made the cover of Time magazine, shaved his hair in the shape of an arrow to point him toward the opposing quarterback.

The Steelers touched some deep emotional chord that stirred a personal creative energy in a diverse ethnic population that had been hungering for a winner.

A Greek showman named Jimmy Pol merged the melody of the Pennsylvania Polka with his own lyrics. That 45 rpm record became the anthem: "We're from the town with the good football team..." The original version included references to the Gorillas and the Army.

Harold Betters and his jazz band serenaded fans at games. His trombone provided the sound track to the chant, "Here We Go, Steelers, Here We Go."

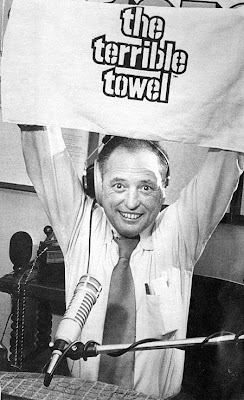

To top it all off, Myron Cope, the wordsmith whose schtick was that of the Yiddish yinzer, turned terry cloth into a trademark with the Terrible Towel.

One all-encompassing banner created back then now graces Heinz Field. It is a proclamation and a warning: You're In Steeler Country.

One all-encompassing banner created back then now graces Heinz Field. It is a proclamation and a warning: You're In Steeler Country.Winning the first one

In a decade that introduced leisure suits and smiley faces and disco, the '70s were a roiling time. The Kent State shootings. Spiro Agnew's resignation and plea of no contest to tax evasion. Paris Peace Accords. Richard Nixon said he was not a crook, then resigned the presidency and was pardoned. Saigon fell. An Arab oil embargo inflated gasoline prices. Billy Carter's brother occupied the White House. Iran held Americans hostage. The Soviet Union prepared to invade Afghanistan. And the Steelers provided a blessed diversion.

After Terry Bradshaw emerged from a bitter and contentious quarterback controversy, all the pieces were in place by 1974 for the greatest stretch of football a football town has ever seen. When the Steelers clinched the division title and a playoff spot by defeating the Patriots, someone asked Chuck Noll where the bubbly was.

"Champagne?" he asked with steely-eyed resolve. "We're interested in rings."

Joe Greene

Joe GreeneAfter the first round of the playoffs, the notion was put forth that the best two teams in football had clashed when Oakland defeated the defending champion Dolphins. But the Steelers coach had a different view, which led to what Joe Greene called the defining moment in Steelers history.

"I have news for them," Mr. Noll told his players before preparations began for Oakland. "The best team in professional football is right here in this room."

He had never said anything like that before or since. And it got the Steelers in a proper froth.

"It made a big impression on me," said Mr. Greene. "We were behind in the fourth quarter on the road, but there was no despair, no anxiety, no worries. Maybe it was foolhardy. I felt personally that Oakland had no chance."

They didn't. And the Steelers earned a spot in their first Super Bowl. They were underdogs going into that Jan. 12, 1975, game against the Vikings, but this was no longer the Old Testament.

Dwight White, who lost 18 pounds in a bout with pneumonia during the week, climbed out of his hospital bed to register a safety and the team's first points in a Super Bowl. Franco Harris ran and ran to claim the MVP award.

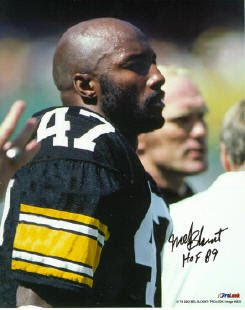

Joe Greene intercepted a pass and recovered a crucial fumble -- "I wasn't prepared to lose," he said -- and captains Andy Russell and Sam Davis elected to give him the game ball. Fate took a hand when Art Rooney was spotted off to the side, stoically waiting to accept the Lombardi Trophy on behalf of his players.

Pete Rozelle presents the Vince Lombardi trophy to Steelers owner Art Rooney after Super Bowl IX.

Pete Rozelle presents the Vince Lombardi trophy to Steelers owner Art Rooney after Super Bowl IX."I saw The Chief standing in a corner, totally removed from the scene, and I just knew that ball should go to him," said Mr. Russell. "I had a lot of good moments with him, but that one was the best."

Thoughts turned to the fans who had waited so long for the ultimate prize.

"The 'Burgh must be in ashes," Jack Ham laughed.

Lynn Swann's breathtaking catches earned him MVP honors the next year in Super Bowl X, a win over the Cowboys that validated the Steelers as true champions. But mention must be made of Jack Lambert, who served notice that there were to be consequences for laughing at Pittsburgh.

With the Steelers trailing, Roy Gerela -- his ribs bruised while making an earlier tackle -- missed a field goal. Cliff Harris got in the kicker's face and taunted him, which prompted Mr. Lambert to toss the Cowboys free safety unceremoniously to the ground.

"We were getting intimidated, and we're supposed to be the intimidators," said Mr. Lambert, who did not draw a penalty for his actions. "Someone had to do something about it."

That play inspired the defense to a second Super Bowl win. It had taken the Steelers 42 years to win their first NFL title and just 371 days for their second.

Said coach Noll: "Jack Lambert is the defender of all that is right."

Said coach Noll: "Jack Lambert is the defender of all that is right."Of all the super teams of the '70s, the best one didn't win a Super Bowl. That 1976 team lost in the playoffs to Oakland because injuries wiped out their running backs.

During a nine-game winning streak, in the hands of rookie quarterback Mike Kruczek taking over for an injured Bradshaw, when a loss would have eliminated them, the defense took command like never before. It posted five shutouts and, in one stretch, didn't allow a touchdown for 22 quarters. The Steelers routed the Colts in the playoffs, but the only back available in the AFC championship game was Reggie Harrison.

The next year, 1977, the Steelers defeated the Raiders in federal court, but the messy proceedings served as a distraction.

Oakland's George Atkinson had sued for slander after Chuck Noll said he was part of a "criminal element" for a hit on Lynn Swann. A jury in San Francisco returned a verdict that exonerated the coach. But the NFL fined him for inappropriate remarks.

The cast was largely the same but a fresh script arrived in 1978, in large measure because the Steelers defense was so dominant. New rules were adopted to create more offense, but they actually served to take the reins off the Steelers passing game. Although Terry Bradshaw may have exasperated critics who thought he was Li'l Abner in cleats and prone to stage fright, he threw the prettiest spiral in the NFL and came up big on the biggest stage.

The cast was largely the same but a fresh script arrived in 1978, in large measure because the Steelers defense was so dominant. New rules were adopted to create more offense, but they actually served to take the reins off the Steelers passing game. Although Terry Bradshaw may have exasperated critics who thought he was Li'l Abner in cleats and prone to stage fright, he threw the prettiest spiral in the NFL and came up big on the biggest stage.After a going 14-2 in 1978 -- a franchise record for wins to that point -- the Steelers breezed through the playoffs for a rematch with the Cowboys, who had been dubbed America's Team by NFL Films.

The tag didn't phase Dan Rooney. "We're Pittsburgh's team," he said.

And after Hollywood Henderson said that Mr. Bradshaw couldn't spell cat if you spotted him the "c" and the "a," the quarterback had his best day as a quarterback in a super win, leaving it up to the Cowboys to spell M-V-P.

The exhilarating roll continued in 1979. Every touchdown pass, every defensive stop, every victory served as a confirmation.

For the second straight year, the Steelers split the regular season series with the Oilers and then beat their rivals in the AFC title game. Houston coach Bum Phillips volunteered these words for his epitaph: "He'd have lived a hell of a lot longer if he didn't have to play Pittsburgh six times in two years."

Mr. Bradshaw repeated as Super Bowl MVP. His biggest contributions were two long passes to John Stallworth -- both of them right on the money -- to rally the Steelers in the fourth quarter over the Rams. The Steelers became the first team to win consecutive Super Bowls twice and the first team to win the big game four times, going from the outhouse to the penthouse in one glorious decade.

Mr. Bradshaw repeated as Super Bowl MVP. His biggest contributions were two long passes to John Stallworth -- both of them right on the money -- to rally the Steelers in the fourth quarter over the Rams. The Steelers became the first team to win consecutive Super Bowls twice and the first team to win the big game four times, going from the outhouse to the penthouse in one glorious decade.After presenting the team its fourth Lombardi Trophy, Pete Rozelle quipped that the value of the sterling silver was higher than the franchise fee The Chief paid back in 1933. Priceless.

The bandwagon was so overcrowded it became a movable tail-gate party. In the background, however, were rumblings that real-life steelers and the mills that employed them were edging toward hard times.

First published on October 7, 2007 at 12:00 am

Next: The '80s

Robert Dvorchak can be reached at bdvorchak@post-gazette.com

No comments:

Post a Comment