Yahoo! Sports

October 12, 2012

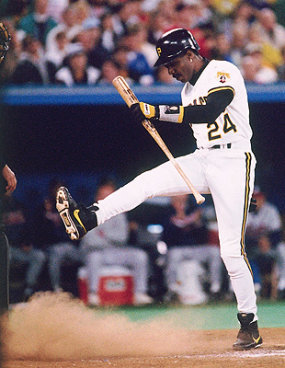

In 1992, Barry Bonds was in the midst of one of the most astonishing performance streaks in baseball history. He had won the MVP in 1990, probably should have won it in '91 and would go on to win it in '92 and '93. He was the centerpiece, if not necessarily the clubhouse leader, of the Pittsburgh Pirates, batting .311 with an OPS of 1.080.

But he was also carrying a woeful .132 postseason batting average, and his reputation as an October no-show was already formed when Francisco Cabrera, the last chance the Atlanta Braves had in Game 7 of the National League Championship Series, lined a single to Bonds in left field. David Justice, standing on third, scored easily to tie the game, and behind him, chugging toward home was Sid Bream.

Twenty years ago Sunday, the race was on between Sid Bream's woefully slow legs and Barry Bonds' left arm in what today remains as one of the most iconic moments in major league baseball history.

The birth of a rivalry

Fun fact: For about 24 hours in 1992, Barry Bonds was an Atlanta Brave. That season, Bonds was in the final year of his contract and made no secret of his intentions to play for a World Series-caliber team. Before the season began, Atlanta's then-general manager John Schuerholz reached a deal in principle that would bring Bonds to Atlanta in exchange for pitcher Alejandro Peña, outfielder Keith Mitchell and a prospect to be named. But Pirates GM Ted Simmons got cold feet, perhaps influenced by Pirates manager Jim Leyland's volcanic reaction at the news, and backed out of the deal.

"In baseball, that's about as sacrosanct as anything gets," Schuerholz later wrote in his autobiography. "That had never happened to me, nor has it since, when there was a total reneging of a trade."

How would baseball history have changed with Bonds in Atlanta? Certainly the Braves would not have had the financial capacity to sign Greg Maddux the next year. And the clubhouse would have been a very different place; Bonds' me-first, me-last ego would not have meshed well with then-manager Bobby Cox's insurance-firm atmosphere.

In the end, it's a moot point. Bonds was the best player on the Pirates roster, a proud club that in 1992 advanced to its third straight National League Championship Series. But it had yet to reach the World Series in any of those attempts. Cincinnati, riding its Nasty Boys relief corps, knocked off the Pirates four games to two in 1990, and the worst-to-first Braves had taken out the Pirates in seven games the next year.

This time around, the Pirates were determined to write a new ending.

Under the guidance of the chain-smoking Leyland, they finished 96-66, nine games clear of the Montreal Expos for the NL East crown. Once again in the NLCS they would face the Braves, who after their historic 1991 season weren't sneaking up on anyone.

The Braves swept the first two games at home, only to have the Pirates win two of three in Pittsburgh then another back in Atlanta setting up a final winner-take-all Game 7 showdown at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium on Oct. 14, 1992.

Though both teams had been there before, they were taking diametrically opposed approaches to the night ahead. The Braves' clubhouse was button-down quiet, while the Pirates were running layup drills on a Nerf basketball hoop.

Then it was time for the first pitch, to be delivered by Atlanta's John Smoltz to Alex Cole. Four pitches later, Cole was on first with a walk. Four batters later, Cole was home with the Pirates' first run. Pittsburgh would add another in the top of the sixth off an Andy Van Slyke single.

Atlanta had opportunities. The Braves loaded the bases with no one out in the sixth, but came away empty. And as the innings wore on, the opportunities melted away.

Pirates starter Doug Drabek continued to baffle the Braves with pitches that ducked in and out of the strike zone, nullifying every threat. By the final frame, the Atlanta fans – already developing a fair-weather reputation – had begun heading for the exits, even though the heart of the Braves order was coming to the plate.

Bottom of the ninth, no outs

Reigning NL MVP Terry Pendleton, who won the award in '91 largely because Bonds was so unpopular, led off the inning, bringing to the plate an 0-for-15 record against Drabek to the plate. But Pendleton raked Drabek's third pitch to the right-field wall, tucking it hard against the foul line, clapping his hands as he stopped at third. Justice was next. After taking a strike, he roped what should have been a routine grounder straight at Jose Lind, the Pirates' usually flawless second baseman. Lind had made only six errors in the regular season and would go on to win the Gold Glove that year, but in Game 7 he made two errors, including a boot of Justice's grounder.

"It could turn out to be the biggest error of his life," CBS announcer Tim McCarver said ominously.

Then came Bream. He was one of the last links to the days of the 1980s, when ballplayers sported cheesy mustaches, amiable demeanors and, well, names like "Sid." A former Pirate himself, he stepped in with men on first and third. With a deafening chant of "SID! SID! SID!" echoing through the stadium and the evidence of Lind's crucial miscue staring at him from first, Drabek walked Bream on four straight pitches, ending his night.

Leyland brought in hard-throwing Stan Belinda to close out the night. The first batter he faced, outfielder Ron Gant, smoked what initially appeared to be a game-winning grand slam deep to left. But as Bonds tracked the ball, he stopped one step from the wall where he made the catch.

Bottom of the ninth, one out

Pendleton scored on Gant's sacrifice, but the Braves still had the tying run, in the form of Justice, standing on second base and unable to advance.

Catcher Damon Berryhill came up next and would have been an ideal double-play candidate, except for two problems: First, Belinda was a flyball pitcher and had only induced a single double play all season, and second, Belinda proceeded to walk Berryhill on five pitches. The fourth ball appeared to curl right inside the strike zone, but umpire Randy Marsh – pressed into home plate duty when John McSherry left the game in the second with chest pains – made no move. (Sadly, McSherry would die on the field in Cincinnati, a victim of a heart attack on Opening Day, 1996.) Berryhill took first as Pirates catcher Mike LaValliere barked at Marsh.

The bases were now reloaded, with the slow-footed Bream carrying the winning run at second. Brian Hunter stepped in to pinch-hit for light-hitting shortstop Rafael Belliard. This is an important detail: Cox had no one left to pinch-run for Bream; he'd already used all his position players, and his fastest pitcher, Smoltz, had started the game.

The Atlanta fans kept up the haunting tomahawk chop chant as players in both dugouts fidgeted. The Braves tried on various permutations of the rally cap, flipping their hats upside-down on their heads, then fitting the brims straight up and sideways like sharks' fins. Over in the Pirates dugout, Drabek slowly stroked at the edges of his Fu Manchu mustache as Leyland stared out at the unfolding debacle in disbelief.

The Pirates dared to hope again, though, as Hunter lofted a soft fly ball into short center field. This time, Lind gloved it without incident and fired it back into the infield; the Braves were unable to advance.

Bottom of the ninth, two outs

The pitcher's spot was up, and Cox was down to his last bench player, backup catcher Francisco Cabrera, who'd had only 10 at-bats all season. "Señor Last Resort," Atlanta Journal-Constitution sports editor Furman Bisher would call him. "A most unlikely man in the spotlight for Atlanta," CBS play-by-play announcer Sean McDonough said as Cabrera dug in against Belinda.

Out in left, Bonds had moved back, intent on keeping every ball in front of him.

"Move in!" Van Slyke shouted from center.

Bonds, Van Slyke would later tell author Jeff Pearlman, reacted in the expected Bonds way: He raised his middle finger.

(No video exists of this moment, which is a shame. If it had happened today, it would be on YouTube before Cabrera finished his at-bat.)

"People forget that Bonds was an excellent outfielder," Pearlman, author of a biography on Bonds, told Yahoo! Sports. Bonds would win a Gold Glove in 1992. "He had great instincts. He wasn't trying to defy Van Slyke. He just thought he knew better what to do out there."

Belinda's first pitch to Cabrera ran far outside, his second flew low. At 2-0, Cabrera still had the green light and hooked a ball foul, deep into the seats past the Pirates bullpen in left. Cabrera cursed himself, adjusted his helmet, then stepped back in to the batter's box as Belinda asked for a new ball.

"All of a sudden, we looked at each other like, 'Hey, Frankie is going to hit this guy,' " Braves shortstop Jeff Blauser recalled in Tomahawk, a book about the '92 Braves by Bill Zack. "Don't ask us how we knew, we just knew."

Belinda took the sign from LaValliere, wound up and let loose a long, looping curve that was headed for the outside corner of the plate. But Cabrera snapped his bat out, impossibly quick, lining the ball right over shortstop Jay Bell's head and almost – but not quite – directly at Bonds.

Justice was running on the crack of the bat, tying the game and ensuring there was more baseball to be played. Bonds had to move two steps to his left for the ball and unloaded a looping shot toward home.

Bream, meanwhile, steamed around third, eyes wide, arms chugging, cranky knees groaning. Those knees had suffered through five operations, all for a moment like this. Justice screamed for Bream to slide. Slide!

Bonds' throw bounced one step up the first-base line. LaValliere grabbed it and dove back toward the sliding Bream. Years later, Atlanta and Pittsburgh fans still debate whether Lavalliere caught Bream before Bream caught the plate. Marsh, though, didn't hesitate.

In the Braves radio booth, legendary announcer Skip Caray would relate the play in a call that has since been replayed roughly a half billion times in Atlanta since: "One run is in! Here comes Bream! Here's the throw to the plate … he is … SAFE! Braves win! Braves win! Braves win! Braves win! Braves win!"

The team mobbed Bream at the plate, Justice the first to reach him. Players, coaches, batboys, reserves – they all piled atop their cement-footed first baseman, who on this night was just … fast … enough.

Final score: Atlanta 3, Pittsburgh 2

As the Braves exulted, the Pirates collapsed. "I'm five-foot-eight," LaValliere said, according to Zack. "If I'm five-foot-eight-and-a-half, he's out."

Van Slyke just sat down in center field, staring at nothing, the last Pirate to leave the field.

"This is probably the hardest lesson I've ever had to handle, and I'm not sure I'm handling it well," Leyland said after the game. "It's a little tough to tell your players three years in a row, 'Thanks for the effort.' This is a real heartbreaker."

The Pirates knew that after three chances, their window had finally closed. Bonds and Drabek were already on their way out the door and with them their best chance of ever getting this far again.

Pittsburgh hasn't had a winning season since.

"I knew in my heart that I would never be in that position again as long as I was a Pirate," Van Slyke would later tell author Jeff Pearlman. "It was my saddest day in baseball. The end of the road."

No comments:

Post a Comment