By

http://www.nytimes.com/

February 6, 2014

Ralph Kiner, baseball’s vastly undersung slugger, who belted more home runs than anyone else over his 10-year career but whose achievements in the batter’s box were obscured by his decades in the broadcast booth, where he was one of the game’s most recognizable personalities, died on Thursday at home in Rancho Mirage, Calif. He was 91.

The Baseball Hall of Fame, which inducted him in 1975, announced the death.

Baseball fans who are short of retirement, especially those in New York, are familiar with Kiner as an announcer who spent half a century with the Mets, enlivening their broadcasts with shrewd analysis, amiable storytelling and memorable malapropisms beginning with their woeful first season in 1962.

His genial, well-informed and occasionally tongue-twisted presence accompanied all of Mets history, from the verbal high jinks of Casey Stengel and the fielding high jinks of Marv Throneberry to the arrival of the fireballer Tom Seaver and the miraculous World Series championship of 1969, from the thrilling 1986 Series victory over the Red Sox to the dispiriting Subway Series loss to the Yankees in 2000 and the Madoff-poisoned, injury-riddled ill fortune of recent seasons.

But long before he referred on the air to Gary Carter as Gary Cooper, declared that “if Casey Stengel were still alive he’d be spinning in his grave,” or watched a long ball disappear from the park with the trademark call “Going, going, gone, goodbye!,” Kiner was one of the game’s great right-handed hitters.

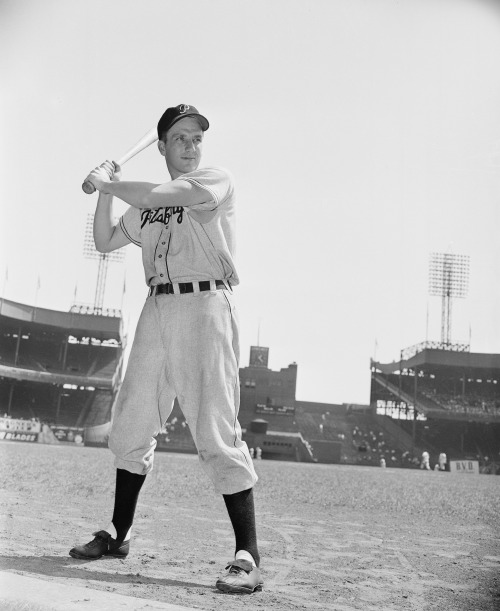

Cut short by a back injury, Kiner’s career on the field was among the most remarkable in baseball history, featuring a concentrated display of power exhibited by few other sluggers. Slow afoot and undistinguished as an outfielder, he was nonetheless among the signature stars of the baseball era immediately after World War II, in the same conversation with Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams and Stan Musial.

From 1946 to 1955, playing for the Pittsburgh Pirates, the Chicago Cubs and the Cleveland Indians, he totaled 369 home runs, twice hitting more than 50 in a season, and drove in 1,015 runs, an average of more than 100 a year.

During his first seven seasons, all with Pittsburgh, Kiner led the National League in home runs every year, still a record streak for either league. (Twice he tied with Johnny Mize, once with Hank Sauer.)

From 1947 to 1951, he had home run totals of 51, 40, 54, 47 and 42, becoming only the second player in history — Babe Ruth was the first — to hit at least 40 home runs in five consecutive seasons, and the third (after Ruth and Jimmie Foxx) to hit 100 over two consecutive seasons.

From 1932, when Hack Wilson hit 56 homers for the Chicago Cubs, to baseball’s steroid era in the 1990s, Kiner’s 54 homers in 1949 was the highest single-season total for a National Leaguer; Henry Aaron never matched him, nor did Willie Mays, Ernie Banks, Mike Schmidt or Willie McCovey, all Hall of Famers with more than 500 career homers.

Kiner never made it to the World Series; the Pirates of his era were perpetually mediocre (or worse), and so were the Cubs. In 1955, traded to the American League for his last season, he got closest: the Indians finished second to the Yankees.

For a time, Kiner was among baseball’s highest-paid players. But after Pittsburgh’s dreadful 1952 season, when the team’s record was 42-112 in spite of Kiner’s league-leading home run performance, Branch Rickey, the Pirates’ general manager, cut his salary, reportedly telling him, “Son, we can finish last without you.”

His short career, along with his longtime residence at the bottom of the standings, perhaps explains Kiner’s relative lack of recognition. When he was finally elected to the Hall of Fame, in 1975, his 15th and final year of eligibility, he sneaked in with 273 votes out of a possible 362, two more than needed for election.

But Kiner was appreciated in other circles. Tall, good-looking and well spoken — as a player, he aspired to the career in broadcasting that came to define him — he was, in the parlance of the era, a highly eligible bachelor. Introduced to Elizabeth Taylor by Bing Crosby, who was a part owner of the Pirates, he escorted her to the Hollywood premiere of the 1949 war film “Twelve O’Clock High,” starring Gregory Peck. When the movie “Angels in the Outfield” (1951) was filmed at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, Kiner dated its star, Janet Leigh.

His courtship of the tennis star Nancy Chaffee, winner of three consecutive national indoor championships, was avidly chronicled by gossip columnists. Their engagement was announced on the radio by Walter Winchell before Kiner actually proposed, and shortly after their marriage, in 1951, the bride wrote an article for The Saturday Evening Post (as told to Al Hirshberg) with the headline “Why I Married Ralph Kiner.”

After she met him, tennis was no longer the most important thing in her life, Chaffee wrote.

“Even if invited, I won’t go back to Wimbledon unless it’s agreeable to Ralph,” she went on. “It’s too far from Forbes Field, where the Pirates play their home games. For that matter it’s too far from the cities I hope to visit as a ballplayer’s wife.”

Kiner and Chaffee had three children in a 17-year marriage that ended in divorce in 1968. Chaffee later married the sportscaster Jack Whitaker; she died in 2002. Kiner’s second marriage, to Barbara George, also ended in divorce. A third marriage, to DiAnn Shugart, ended with her death in 2004. His survivors include his sons Ralph and Scott; his daughters Kathryn Chaffee Freeman, Tracey Jansen and Kimberlee Manzoni; and 12 grandchildren.

Ralph McPherran Kiner was born in Santa Rita, N.M., on Oct. 27, 1922. His father, a baker, died when Ralph was 4, and he moved with his mother, Beatrice, a nurse, to Alhambra, Calif., where he grew up playing ball. He signed with the Pirates after graduating from high school, playing two seasons and part of a third in the minor leagues before training as a Navy pilot during World War II. He served in the Pacific, assigned to search for Japanese submarines, though he acknowledged he did not see combat — or much else.

“I was on a few patrols but, gosh, we didn’t even spot a whale,” he told The New York Times in 1947.

At the start of that year, his second in the big leagues, the Pirates acquired the great slugger Hank Greenberg from the Detroit Tigers, and Greenberg became Kiner’s roommate and mentor (and later his best man at his wedding to Chaffee), advising him on his swing, his preparation, his work ethic.

Greenberg’s acquisition helped Kiner in more tangible ways as well. For one thing, Greenberg hit behind him in the batting order, protecting him, making sure he got better pitches to hit, and Kiner hit .313, the highest average of his career. What’s more, to accommodate Greenberg, the Pirates had modified Forbes Field, moving in the left field fence to bring it in line with other ballparks and installing the bullpens behind it, an area that came to be called Greenberg Gardens for the long balls the new Pirate was expected to plant there.

But it was Kiner who was the primary beneficiary of the change, hitting 51 home runs. Playing what turned out to be his last season, Greenberg hit 25. Greenberg Gardens was rechristened Kiner’s Korner.

The two men were reunited in 1955, when Greenberg, then the general manager of the Indians, acquired Kiner from the Cubs, a transaction complicated by Kiner’s curious decision to sign a contract for $40,000 a year, less than he was offered and far less than he made the previous year in Chicago, reported to be $65,000.

Major league player representatives objected to the contract because it violated the agreement between players and club owners that a player’s salary could not be reduced by more than 25 percent in a season. Baseball’s commissioner, Ford C. Frick, indicated that he would void the contract, and Kiner and Greenberg, who did not want to pay him so little in the first place, eventually renegotiated it.

“I did not have too good a year with the Cubs, and my salary might have been resented by some players,” explained Kiner, who was among the players who fought owners for an improved pension plan. “I thought if I had a good season with the Indians in 1955, I could more than make up the cut the following year. At first Greenberg was against it, but he then thought the publicity would be good. At no time did I have in mind to undermine the players. Everyone knows I’ve been fighting for them for years.”

In Cleveland, his back problems worsened. He played only 113 games for the Indians in 1955 and hit a career-low 18 homers, prompting his retirement. For five years afterward he was general manager of the San Diego Padres, then a minor league team, and in 1961 he got his first broadcasting job, calling games on the radio for the Chicago White Sox. The next season the Mets began life in New York, and he was offered a job on their broadcast team, he once said, “because I had a lot of experience with losing.”

Over half a century of Met broadcasts, while sharing the microphone with Lindsey Nelson, Bob Murphy and Tim McCarver — whom he once called Tim MacArthur — among many others, Kiner proved himself especially valuable in explaining the nuances of hitting, and though occasionally criticized for a flat affect and a penchant for phrase-bungling — “On Father’s Day we again wish you all happy birthday!” — he was known as an amusing raconteur who was generally well prepared with both facts and stories, and his intended wit was often as memorable as his unintended humor.

“Two-thirds of the earth is covered by water,” he declared about an especially fleet outfielder. “The other third is covered by Garry Maddox.” Cutting to a commercial after mistaking McCarver’s name for that of the World War II general, he said: “MacArthur once said ‘I shall return,’ and we’ll be back after this.”

In addition to his game broadcasts, he was the host of the popular postgame interview show “Kiner’s Korner,” itself a source of legendary Kinerisms, though he was sometimes outdone by his guests. In one exchange from the early days of the Mets (though not on the show “Kiner’s Korner”), he asked a young Mets catcher, Choo Choo Coleman, “What’s your wife’s name, and what’s she like?” Coleman replied, “Her name is Mrs. Coleman — and she likes me, bub.” (Years later, Coleman denied this ever happened.)

In 1996 Kiner disclosed he had Bell’s palsy, but he continued to work, albeit with slurred speech. In later years he appeared on broadcasts only sporadically.

In 2010 Kiner was described in The New York Times as “a human archive of Mets and baseball history,” and indeed he had the kind of longevity in the game that allowed him to put one career in perspective as he began his second. In 1961, as Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle pursued Babe Ruth’s record of 60 home runs in a season, achieved in 1927, Kiner recalled that in 1949, when he was chasing the same mark, it was so revered that he dreaded breaking it. He’d even written a magazine article under the headline “The Home Run I’d Hate to Hit.”

“Twelve years after I had my 54-homer season, I find myself saying that I wish I’d broken the Babe’s record,” he said, going on to predict, wrongly, that Ruth’s career record of 714 home runs would never be broken. (Henry Aaron and Barry Bonds have both done so.) He could not have known that a new chance at fame awaited him on the airwaves, but he already felt that his accomplishments on the field had faded to obscurity.

“I’ve reached a point now that I’m surprised when I’m asked for an autograph,” he said. “Yesterday doesn’t count anymore, only today.”

No comments:

Post a Comment