BY JOE STARKEY

June 23, 2016

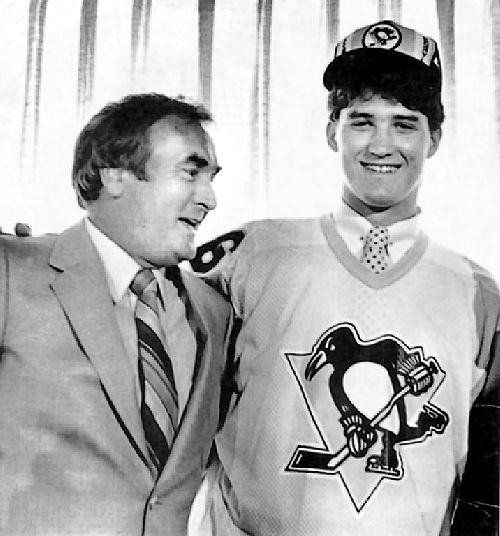

Ed Johnston and Mario Lemieux

At some point, lower in this space, we'll talk about how the original captain of the Philadelphia Flyers became an all-time Penguins hero, albeit a forgotten one.

We'll talk about how that parade last week never happens without him. And how there is no Sidney Crosby here. No Mario Lemieux. No Stanley Cups.

But let's start with the concept of tanking in pro sports, because it's not going anywhere, no matter how many lottery systems leagues devise.

To the contrary, it seems more prevalent than ever ...

• In baseball, nearly half the National League has been accused of essentially forfeiting this season (not including the Pirates, who are just making it look that way).

• In the NBA, the Philadelphia 76ers are engaged in a brazen, multiyear tanking project.

• In the NHL, the Toronto Maple Leafs will step to the podium Friday in Buffalo (where the Sabres flagrantly sabotaged their 2014-15 season) and select coveted center Auston Matthews first overall on account of a nearly flawless tank job combined with the luck of winning the draft lottery.

• In the NFL, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers won the first pick in 2015 (Jameis Winston) by losing in spectacularly intentional fashion in their 2014 finale. They blew a 13-point lead to the New Orleans Saints by benching nearly all of their best players.

The line between “tanking” and “rebuilding” always has been blurry. I embrace the practice, however it's phrased, because the last place you want to be is mired in perpetual OK-ness. You don't want to be the Atlanta Hawks.

What's more, I've always found that tanking makes for riveting theater. Watching how teams go about losing can be more fun than monitoring the top of the standings.

There is an art to tanking. It invariably starts upstairs, where a GM can manipulate a roster. It gets murkier, and harder to defend, when coaches start making questionable moves.

Take the 2005-06 Minnesota Timberwolves, who needed to finish in the NBA's bottom 10 to keep their first-round pick. In their final game, a narrow defeat, the Wolves sat Kevin Garnett and others for no apparent reason and let legendary scrub Mark Madsen fire nine 3-pointers after attempting none all season.

Afterward, Wolves coach Dwane Casey said his guys “deserved to have a little fun” after all they'd been through.

“I hope what we did didn't make a mockery of the game,” Casey said.

Mockery? What mockery?

All of which brings us to Casey's spiritual predecessor, Mr. Louis Frederick Angotti, coach of the 1983-84 Penguins and the forgotten hero I mentioned earlier.

If you know anything about Penguins history, you know the '83-84 club finished with a league-worst 38 points and thus won the right to draft Mario Lemieux. There was no lottery. The Penguins needed to finish lower than the horrid New Jersey Devils, and general manager Ed Johnston made sure it happened — by just three points — through a variety of curious-to-laugh-out-loud roster moves.

It might have been the greatest legal tank job in sports history.

But whereas Angotti will readily tell you the Penguins tanked, Johnston will go to his grave never admitting it. Just a few weeks ago, during the Stanley Cup Final, I asked him if he ever told Angotti to lose on purpose.

“(Expletive) no,” he said. “People paid money for those games. Nobody's going to tell anybody to lose. We had no talent.”

When I told E.J. that Angotti admittedly made moves to lose on purpose, he said, in his good-natured way, “He did? I don't remember that.”

But then E.J. added, with a dash of defiance, “You're going to try to win an extra game or two at the end and lose the first pick when it's Mario Lemieux?”

Of course not. Johnston is rightly considered a Penguins savior for doing what he did.

1968 Topps

Angotti has no such “pride of place” in team history, as Michael Farber put it a few years ago in his outstanding TSN documentary on those pathetic Penguins, titled “Playing to Lose.” Angotti's just a guy with a horrible career record (22-78-12, including a stint in St. Louis) who never coached another game after '83-84, though he remained with the organization for a year.

Now 78, Angotti has been living a comfortable retired life in Pompano Beach, Fla., after many years as a stockbroker there. Before entering the financial world, he opened a bar called Pickles, which was fitting, considering the pickle he found himself in when he took the Penguins job.

Though the team was beyond awful, there were no designs on tanking, Angotti told me, until he, Johnston and broadcaster Mike Lange went to watch Lemieux play a junior game during the Penguins' late-January trip to Montreal.

“Everybody was trying to stop him, and I think he had five breakaways,” Angotti said.

Days later, at one of their customary breakfast meetings, Johnston and Angotti hatched a general plan.

“(Johnston) said, ‘We're going to do whatever we possibly can to put ourselves in position to draft Mario Lemieux, and there's a very good chance it will cost us our jobs,' ” Angotti recalled. “I said, ‘Fine, I think it's the right thing to do.' ”

So this is where we'll pause, barely a week after the Penguins paraded the Cup in front of more than 400,000 adoring fans, and consider the sacrifice.

Johnston and Angotti were hockey lifers — Angotti a small but spirited player who became captain of Philadelphia's expansion team, Johnston the last goalie to play every minute of every game in a season (despite a torn ear lobe, three broken noses and 70 stitches). Yet there they sat, resolving to stuff their pride, go against all their teachings, take a bunch of flak and lose as many games as possible for the chance to win later — knowing someone else likely would reap the benefits.

Someone else did. Neither man was with the team when the Penguins finally returned to the playoffs in 1989.

“I don't think anybody else would have done what Eddie Johnston did,” Angotti said.

What about you? I wondered. Would any coach have done what you did?

“I don't think so,” he said. “I'm convinced of that. I don't think anybody would have put their jobs on the line like we did.”

What, precisely, did Angotti do? He said he would put the wrong players on the ice in special teams situations or send his fourth liners out against stars. He said he once pulled starting goalie Roberto Romano in a game the Penguins were winning and wound up with a valuable loss.

“It was tough waking up in the morning,” Angotti said. “It didn't make me feel very good. It was far more strenuous trying to figure out (how to lose) than it would be trying to play a normal game. I remember we got a penalty, and I sent out two players I wouldn't normally put out there. One player yelled to me, ‘Louie, what the hell are you doing?' It was almost an ongoing thing.

“If the game started off badly, there wasn't much for me to do. It was the games where we were competitive and looked like we were going to win where I was in position to put us in a position to lose. The only thing you could do is manipulate your bench, use whatever you had on the bench to put yourself in a position to lose.

“I can honestly say the players who came to work every day gave all they had. That was the tough part. I was playing against them. It was me against them, them against me. They were trying to go out and win, and I was using them to lose.”

Wow. Take that in. If you find it tough to digest, as I do, consider the likely alternative: Pittsburgh with no Penguins. Two more wins, and that very likely would be the case. I read that quote to Gary Rissling, a small, rugged winger from the '83-84 team, a player in the Lou Angotti mold.

Rissling paused and said, “Did Louie say that?”

I assured him he did.

“If Louie said that,” Rissling said, “then it's pretty much the truth.”

Though he remains close to Johnston, the two visiting in Florida from time to time, Angotti never has returned to Pittsburgh. He has turned down invites to coaches' reunions and the like. His memories of this place hurt too much — and the pain is about way more than losing games. He lost the older of his two sons, Jeffrey, to a car accident during training camp in 1983.

Rissling maintains a healthy respect for Angotti.

“Lou was a very good coach in the minors,” Rissling said. “And when he played, he was like me — 5-foot-nothing with a big heart. Louie doesn't like losing. E.J. doesn't like losing. These are guys who played when hockey was six teams. They know what it takes to win.”

And they knew what it took to lose: a combination of foresight and rare fortitude. So keep a kind thought for Lou Angotti during your post-Cup revelry, won't you?

Joe Starkey co-hosts a show 2 to 6 p.m. weekdays on 93.7 FM. Reach him at jraystarkey@gmail.com.

MORE PENGUINS/NHL

No comments:

Post a Comment