By Gene Collier

Wednesday, September 05, 2007

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

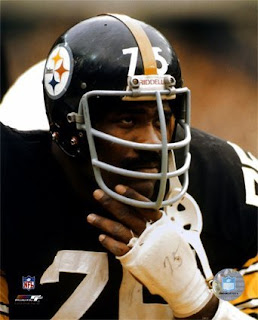

Joe Greene -- "Probably, if I could say anything on my behalf, and I don't mean to do it, but something that I brought to the table that was helpful was an attitude."

Joe Greene -- "Probably, if I could say anything on my behalf, and I don't mean to do it, but something that I brought to the table that was helpful was an attitude."Here at the arrival of the Steelers' 75th season and all its appropriate commemorative elements formal and otherwise, the common urge to summarize in purely football terms must be served.

Fan voting for the all-time Steelers team, for example, has been completed and will have its unveiling in late fall, with few surprises expected. To ensure that players from the '70s forward don't dominate the celebration the way they often dominated the opposition, a separate Legends Team of pre-70s standouts has been selected by special committee and will be introduced at the home opener Sept. 16.

The methodology for selecting the best Steelers was no doubt a lot more legitimate than the methodology I used in nudging the issue to its narrowest point, to the matter of who is the greatest Steeler.

My own flawed system was at least rooted in the great oral traditions of sports, the technical terms ranging from shooting the breeze to chewing the fat. There aren't a lot of people you can ask to identify the greatest Steeler who can speak with the authority of an approximate half-century or more of observation. But there are a handful.

So this summer in Latrobe, long about fat chewing time, I asked most of those with the appropriate gravitas: Dan Rooney, whose life traverses every single Steelers game played; Art Rooney Jr., three years Dan's junior and a certified dynastic architect; Bill Nunn, the legendary scout now in his 40th season with the organization; Dan's sons Art II and Dan Jr., ball boys during the glory days who've since taken critical roles within the organization, Art II as president.

So this summer in Latrobe, long about fat chewing time, I asked most of those with the appropriate gravitas: Dan Rooney, whose life traverses every single Steelers game played; Art Rooney Jr., three years Dan's junior and a certified dynastic architect; Bill Nunn, the legendary scout now in his 40th season with the organization; Dan's sons Art II and Dan Jr., ball boys during the glory days who've since taken critical roles within the organization, Art II as president.The fact that they all identified the same player independently of each other was only half as startling as the amount of time each of them took to consider the question, which was not much.

Joe Greene is the greatest Steeler.

You might disagree, but on the authority of those who've seen the most Steelers football, who've looked at it more analytically as any of us can even have pretended to, there was no Steeler equal to Mean Joe.

Not only might you disagree, but Joe Greene himself, predictably, disagrees.

"My favorite is Franco," Joe said on the phone from Texas the other day. "I guess that's because he was probably the best. We didn't win anything before him and it took a lot of years for us to win anything after him; I'm talking about Super Bowls now."

Compelling testimony, but Joe isn't all that interested in prolonging the argument, especially given the eminence of the electorate.

"Oh, I'm honored, for sure," he said, "but when we start trying to reflect, sentiment starts to play a part in it. I don't mean that in a negative way. It just comes into play. It's because I was tied to Chuck Noll and his first year, and almost tied to the beginning of Three Rivers Stadium; I missed that by one year. In those early years, it was easy to take note of some of my antics. I guess I'm tied to that, too.

"Oh, I'm honored, for sure," he said, "but when we start trying to reflect, sentiment starts to play a part in it. I don't mean that in a negative way. It just comes into play. It's because I was tied to Chuck Noll and his first year, and almost tied to the beginning of Three Rivers Stadium; I missed that by one year. In those early years, it was easy to take note of some of my antics. I guess I'm tied to that, too."Probably, if I could say anything on my behalf, and I don't mean to do it, but something that I brought to the table that was helpful was an attitude."

Attitude is actually where the electorate kind of split. When Nunn said Greene was the greatest because he made every one around him better, I thought he was talking about leadership.

"No," Nunn said. "I mean in the defense. He made Fats Holmes a better player, made L.C. Greenwood a better player, made Jack Lambert a better player. Teams had to put almost all their focus on him."

Even at that, of course, Greene dominated. He was named to 10 Pro Bowls, more than any Steeler, even if his influence is better remembered in singular bursts of destruction.

"He changed everything," said Dan Rooney, suggesting that Greene did as much with demeanor as with muscle for an organization still pretty much steeped in failure when it made Greene the fourth pick of the 1969 draft. It would become clear soon enough that the franchise was looking to Joe Greene for more than menace.

"After a while, this could have been early '71 or '72, what Chuck Noll was saying just started to become part of my consciousness," Greene said. "In '69, and '70, I really didn't want to hear it. What he was saying really wasn't translating into wins. He'd say things like if we stop the run, we'll put ourselves in position to rush the passer. I wasn't a believer, but I became one."

For all of Noll's brilliance, for all of his accomplishments, belief in him within the organization was eventually challenged and ultimately faded. The belief in Joe Greene never did, not in the spring of 1969, not in the summer of 2007.

"He was," said Art Rooney Jr., "the cornerstone, the man, El Cid."

First published on September 5, 2007 at 12:00 am

Gene Collier can be reached at gcollier@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1283.

No comments:

Post a Comment