Tuesday, January 22, 2008

In the wake of the Patriots' victory Sunday, the world of sports commentary is full of phrases like "on the precipice of football history." They are followed by portentous Roman numerals in connection with the impending Super Bowl. It's as if Caesar himself will officiate. Apparently, we are all very lucky to be alive to see it.

The overwrought prose of my trade got me to thinking about just where football history ranks in the pantheon of histories - say, American or African or Asian, modern or ancient, ideas or events.

The initial instinct, admittedly, is to say that the history of a single modern sport might pale in significance to other human histories and suggest our fascination with it a tad overblown. But I happen to be reading the galleys of a book to be published next month by the pathologist who wrote the first paper in a peer-reviewed scientific journal linking repeated concussions in football to a horrible decline and death.

In Play Hard, Die Young, Dr. Bennet Omalu writes a sort of mystery story, particularly suited to this era of CSI mania. He has brain tissue from three former football players who suffered bizarre descents and deaths at relatively young ages. He must figure out why.

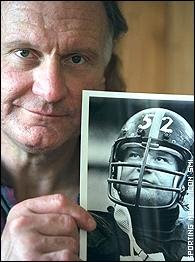

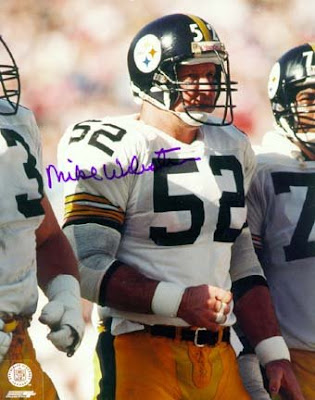

In Play Hard, Die Young, Dr. Bennet Omalu writes a sort of mystery story, particularly suited to this era of CSI mania. He has brain tissue from three former football players who suffered bizarre descents and deaths at relatively young ages. He must figure out why.On some level, most football fans processed the sad story of Mike Webster's decline after a Hall of Fame career as a center for the Steelers. By the time of his induction speech in Canton, he was already having mental problems.

Omalu tells the heartrending story of Webster arising from the dinner table one night, in front of friends and family, opening the oven door and urinating in the oven, believing it to be a commode. Of his 17-year-old son putting a flag on the porch so his dad might recognize their home. Of his marriage dissolving. Of eventual paranoia and homelessness. Of loved ones having no idea why any of it was happening.

The most heavily publicized part of Webster's story was the NFL's refusal to grant him disability benefits for most of his life, perhaps the most shocking example of a heartless system that is only now being embarrassed into reform.

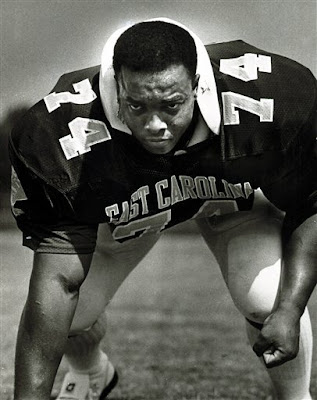

Less well-publicized were the deaths of Terry Long, an offensive lineman who played beside Webster in Pittsburgh, and Andre Waters, a fearsome defensive back for the Eagles. Long and Waters experienced declines similar to Webster's - a loss of cognitive ability and mood stability along with a growing paranoia.

Long was 45 when he killed himself by drinking antifreeze. Waters was 44 when he shot himself in the mouth.

Omalu is a Nigerian-born forensic pathologist who landed in Pittsburgh and was doing about 130 brain autopsies a year in the normal course of his practice. Webster and Long arrived in his lab requiring autopsies. He sought out brain samples from Waters.

Terry Long

Although all three brains appeared normal, Omalu reported that detailed tissue analysis revealed the presence of a form of dementia caused by repeated concussions. Omalu dubbed it "gridiron dementia," similar to dementia pugilistica, or punch-drunk syndrome, which affects boxers. The brain tissue, Omalu reports, resembled that of an 80-year-old dementia patient.

"The brains of boxers who suffer from dementia pugilistica, the brains of three retired NFL players, and the lives of other retired football players who have suffered from dementia are telling us that the way we look at concussions may not be correct," he writes.

"These brains and lives are telling us that certain types of individuals may not recover completely from concussions. Obvious clinical signs and symptoms may not be grossly present, but the brain cells may not recover bio-chemically at the sub-cellular level."

You may not be surprised to learn that the NFL has fought him every step of the way. In fact, NFL doctors tried to get his first paper, on the Webster case, retracted from the medical journal Neurosurgery, which declined their appeal.

"Some of my colleagues and I have wondered if the NFL was adopting a strategy that may be similar to the denial or coverup of the harmful effects of cigarette smoking by the tobacco industry," Omalu writes. "We honestly do not know."

John Mackey

A year ago, the NFL and players association established the "88 plan" in honor of Hall of Fame tight end John Mackey, who was diagnosed with dementia at age 59. It provided up to $88,000 a year for nursing or day care for former players suffering from dementia. Within three months, 54 retired players had applied for aid from the plan.

In the general population ages 60-69, dementia occurs in 66 out of 100,000 people, Omalu reports. With fewer than 10,000 living retired NFL players, the rate of application for the 88 plan suggests a rate at least 10 times greater.

Omalu's disturbing manuscript gives me a new appreciation for the "precipice of football history." Invocation of the Roman gladiators may not be so far off.

kriegerd@RockyMountainNews.com

No comments:

Post a Comment