By Bruce Markusen

https://www.fangraphs.com/tht/cooperstown-confidential-danny-murtaugh-and-the-hall-of-fame/

December 4, 2009

Casey Stengel and Danny Murtaugh in the 1960 World Series (Getty Images)

Whitey Herzog, Davey Johnson and Billy Martin have drawn most of the headlines of the managers listed on this year’s Hall of Fame ballot, but none has a stronger case for Cooperstown enshrinement than a far less publicized fellow. Of all the former managers listed on the Veterans Committee ballot, the late Danny Murtaugh is as deserving as anyone.

I can hear the arguments against Murtaugh already. “Murtaugh, wasn’t he the guy who looked like he was sleeping in the dugout?” Or, there’s the one that has become a common refrain in recent years: “Murtaugh just doesn’t feel llike a Hall of Famer.” Those kinds of reactions will happen when the manager is more laid back than fiery, doesn’t self-promote, and spends his entire career managing in a small market. But a closer look at Murtaugh, in terms of statistical achievements and testimonial and anecdotal support, yields a far more enlightening picture.

In assessing a manager’s worthiness for the Hall of Fame, three statistical measures seem the most important to me. They should not be construed as the final word on a manager’s candidacy, but rather as a simple tool in providing a snapshot of a manager’s career. These measures include the number of world championships, the number of postseason visits relative to the number of seasons managed, and the manager’s winning percentage in the regular season. Murtaugh grades well in all three categories:

World Championships: Winning a World Series is difficult. For managers, winning multiple world championships is exceedingly hard. (Just ask supporters of Herzog, Johnson and Martin, who each claimed one World Series) Only eight managers have won three or more World Series. Of those eight, seven are in the Hall of Fame. The eighth, Joe Torre, will join them shortly after he retires from managing.

Thirteen managers have won exactly two World Series, including Murtaugh. Of those, six are members of the Hall of Fame (Frank Chance, Bucky Harris,Tommy Lasorda, Bill McKechnie, Billy Southworth and Dick Williams). Of the seven who are not in the Hall of Fame, three are still active (Terry Francona,Cito Gaston and Tony LaRussa). That leaves four men on the outside looking in:Bill Carrigan (who had an overall won-loss percentage below .500), Ralph Houk,Tom Kelly (whose career record was also below .500), and Murtaugh. So Murtaugh is in pretty rare company. And though a minimum of two world championships does not—and should not—guarantee someone a place in Cooperstown (13 of 21 have made it thus far), it does at least put you into the argument.

Perhaps Murtaugh also should receive some extra credit here for the kind of world championships he won as manager. In 1960 and 1971, the Pirates entered the World Series as substantial underdogs to the Yankees and Orioles, respectively. In spite of early Series deficits—they were down two games to one in each Series—Murtaugh’s teams managed to come back, completing two of the most stunning upsets in Series history.

Postseason frequency: Since Murtaugh’s career was split between the league and division formats, we have to be careful here. After all, from 1969 to the current day, it has become easier to make the postseason than it was for those managers who worked in the days before the four divisions were created.

Of the 19 men who have been elected to the Hall of Fame as managers, six had careers that included significant stretches from 1969 on. So let’s compare Murtaugh to this “Super Six.”

Manager: Postseason app/overall seasons Percentage

Earl Weaver (six out of 17) 35 per cent

Tommy Lasorda (seven out of 21) 33 per cent

*Danny Murtaugh (five out of 15) 33 per cent

Walter Alston (seven out of 23) 30 per cent

Sparky Anderson (seven out of 26) 27 per cent

Dick Williams (five out of 21) 24 per cent

Leo Durocher (three out of 24) 13 per cent

Murtaugh does well among the managers in this grouping. He ranks behind only Weaver, is tied with Lasorda (who does beat him on longevity), and ranks ahead of heavy hitters like Alston and Anderson. All in all, Murtaugh holds his own with the established Hall of Fame managers.

Winning percentage: In chalking up 1,115 victories over 15 seasons, Murtaugh compiled a winning percentage of .540. How does that compare to the Hall of Fame managers? If put on a list with the 18 major league managers in the Hall (excluding Negro Leagues great Rube Foster), Murtaugh would rank 10th overall in percentage—smack dab in the middle. Murtaugh falls in line behind such legends as Joe McCarthy, John McGraw and Miller Huggins, who help form the upper tier of Hall of Fame managers. But Murtaugh ranks ahead of luminaries like Lasorda, Williams, Bill McKechnie and Casey Stengel. All things considered, Murtaugh does not fare as well as he did in postseason frequency, but still manages to beat half of the field.

All right, enough with the numbers. Now let’s get to the fun stuff. The impact of any manager can be graded only in part through statistical achievement. Other factors, more subjective and anecdotal, need to be considered. Did a manager oversee a cohesive clubhouse? Did his teams improve in relation to the previous manager’s work? Did the manager make positive changes? Was he innovative? Did he change the game in any way?

When Murtaugh assumed command of the Pirates in the middle of the 1957 season, the franchise was fractured, partly because of resentment between the white players and the few minorities on the team. Murtaugh quickly changed the clubhouse culture, unifying the team and producing positive results immediately. Taking over a team that had gone 36-67 under Bobby Bragan, Murtaugh guided the Bucs to a record of 26-25 the rest of the way. The turnaround continued the following season, as Murtaugh went 84-70 in his first full campaign as manager. Murtaugh’s strong influence reached a peak two years later, as the Pirates won the National League pennant with 95 victories before stunning the powerhouse Yankees in the World Series.

The Pirates fell off badly in three of the next four seasons, culminating in Murtaugh’s resignation for health reasons after the 1964 season. Yet, he would return to the Pirates helm on three different occasions, with the team improving its record two of the times. When Murtaugh took over the Pirates for his third stint in 1970, he succeeded Larry Shepard, whose tenure had been marked by in-fighting. Murtaugh succeeded in molding a divisive clubhouse into a more familial unit. As writer Jimmy Cannon described the Pirates: “It was a cranky team under Harry Walker and Larry Shepard. Guys didn’t get along. They complained and split into grumbling factions. But Murtaugh appears to have straightened them out. The tension isn’t obvious anymore.”

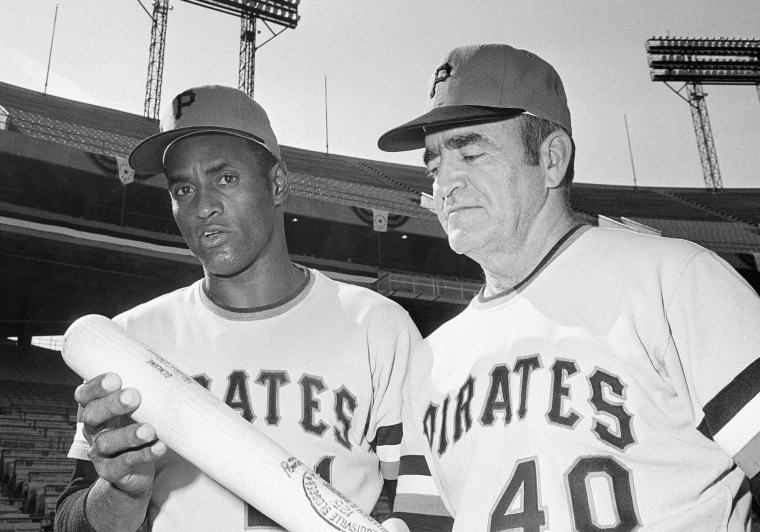

Roberto Clemente and Danny Murtaugh during the 1971 World Series in Baltimore (AP)

Murtaugh’s third stint in Pittsburgh also brought resolution to one of his few shortcomings as a manager. During his first two tenures in Pittsburgh, Murtaugh had struggled in his relationship with Roberto Clemente. Believing Clemente to be a hypochondriac, he often questioned the severity of his injuries. As a result, Clemente grew to distrust Murtaugh. But by the end of the 1970 season, Murtaugh and Clemente had developed a peaceful coexistence. Though still not close friends, the two men came to understand each other’s importance. Murtaugh recognized Clemente as the leader of the clubhouse, a realization that made the manager’s job easier. He began to confide in Clemente, knowing that Roberto could pass along important messages to the rest of the players.

The Pirates’ other resident star had long since regarded Murtaugh as an ally. In a revealing interview with the Newark Star Ledger, Willie Stargell praised Murtaugh as a role manager. “If I were a manager,” Stargell said, “Danny Murtaugh is the kind of manager I’d want to be like. He doesn’t demand respect; he commands it. He knows how to handle players, to get the most out of them. He doesn’t say much, but when he does, you listen because you know it means something.”

Even the most controversial of the Pirates supported Murtaugh wholeheartedly—including the issue of race. “Murtaugh’s a beautiful dude,” the outspoken Dock Ellis once told Sport magazine. “Beautiful. Winning. That’s all he cares about. Nothing else. Screw up, you hear about it. Black or white.”

Murtaugh’s color-blind attitudes might have contributed to a piece of baseball history. On Sept. 1, 1971, Murtaugh fielded the first all-black lineup in the major leagues. Murtaugh tried to downplay any special intent at the time, but some of the Pirates I’ve talked to believe that the manager knew exactly what he was doing in making out a lineup card of nine minorities. If so, Murtaugh showed a kind of fortitude and courage that other managers lacked. Less than a month and a half later, those fully integrated Pirates concluded the season with a monumental World Series upset of the Orioles.

In terms of being a psychologist, a player’s manager, and a father figure to his Pirate players, Murtaugh succeeded masterfully. Yet, he did receive his share of criticism from the media for being too laid back, for being too hands off in his managerial style. There may be some legitimacy to that argument. Murtaugh did not fiercely adopt the running game like Martin did in some of his managerial stops. He did not motivate in the manner that Williams did in Boston, Oakland or San Diego. Nor did he embrace the use of statistics like Weaver did with the Orioles.

Yet, Murtaugh did more than simply make out a lineup card and watch the game unfold. Working with pitching staffs that lacked dominant starters, Murtaugh mixed and matched his bullpen beautifully in 1970 and ’71. It was Murtaugh who decided to convert Dave Giusti from a starter to fulltime reliever; the palmball specialist emerged as one of the best firemen of the early ’70s. Murtaugh also developed talent in Pittsburgh; young players like Willie Stargell (in the early 1960s), Manny Sanguillen, Bob Robertson, Dave Cash, Richie Hebner and Dock Ellis thrived under his guidance. In later years, Dave Parker and John Candelaria emerged on Murtaugh’s watch. Murtaugh’s patient hand with young players became a trademark of his last two tenures in Pittsburgh.

In closing my argument for Murtaugh as a Hall of Famer, I’ll refer to the words I used at the end of my book on the 1971 Pirates. They summarize my thoughts on the value of Daniel Edward Murtaugh:

“Throughout his career, the humble Murtaugh downplayed—perhaps even underestimated—his own managerial skills. While he was blessed with a large supply of talent during his various terms of office in the 1970s, Murtaugh was smart enough not to undermine the success rates of those Pirates teams. And given the unpredictability of baseball in general, and the penchant for player performance to fluctuate wildly from year to year, the Pirates’ record under Murtaugh indeed stood as a testament to his ability to extract the most from his players. The ‘Whistling Irishman’ never overmanaged, and his teams rarely underachieved.”

References & Resources

The Team That Changed Baseball, by Bruce Markusen

The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers, by Bill James

Bruce Markusen has authored seven baseball books, including biographies of Roberto Clemente, Orlando Cepeda and Ted Williams, and A Baseball Dynasty: Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s, which was awarded SABR's Seymour Medal.

1 comment:

I agree with what Bruce Markusen says in this article. If somebody deserve this kind of recognition is Danny Murtaugh.

Post a Comment