"It was all fun . . . You got close with everybody"

Sunday, October 14, 2007

By Gary Tuma, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

This story from the Post-Gazette archives was first published on August 26, 1988.

He was called America's Greatest Sportsman, the World's Most Down-To-Earth Millionaire, and the Man Without an Enemy.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Byron "Whizzer" White once called him "The finest man I've ever known."

When Arthur Joseph Rooney Sr. died yesterday morning at the age of 87, it left a huge void in the Pittsburgh sports scene and in the hearts of the thousands who knew him.

He was pronounced dead at 7:45 a.m. yesterday in Mercy Hospital, where he was taken Aug. 17 after suffering a stroke at the Steeler offices. Initially, Rooney showed progress, but his condition worsened Monday. He fell into a coma and never regained consciousness.

The cigar-chewing founder, principal owner, and chairman of the board of the Pittsburgh Steelers had been a fixture in this city since the 1920s, when he operated several semipro football teams, played semipro baseball, and was an undefeated AAU boxing champion.

In 1933, he brought the National Football League to Pittsburgh when he purchased a franchise for $2,500. The team became the cornerstone of a family sports empire that included horse-racing tracks in Pennsylvania and New York, and dog-racing tracks in Florida and Vermont, as well as a 350-acre thoroughbred breeding farm in Maryland.

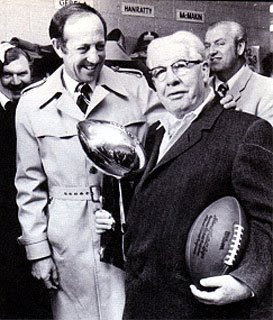

Rooney suffered for 40 years without an NFL championship, but when the Steelers won four Super Bowls in the 1970s and were acclaimed the greatest professional football team to that time, sports columnists nationwide said Rooney's good fortune was proof that nice guys don't always finish last.

Since Chicago Bears' owner George Halas died in October 1983, Rooney had been the elder statesman of NFL owners, the only one whose involvement began in 1933, when the league was organized in modern form.

He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1964.

By the late 1960s, Rooney had turned over day-to-day operation of his sports enterprises to his five sons. Eldest son Dan is president of the Steelers. Second-oldest son Art Jr. is vice president of the team and handles other family investments, primarily real estate.

Third son Tim manages Yonkers Raceway, the family harness track in New York. Pat operates Palm Beach Kennel Club, the dog-racing track in Florida, and Green Mountain Kennel Club in Vermont. Pat's twin brother John also was involved with the family track operations for years and now handles family oil, gas and real estate interests.

The family also operates Shamrock Stables, a farm in Woodbine, Md., and once owned Liberty Bell thoroughbred track in Philadelphia.

Rooney kept close watch on his business empire. Even in the final years of his life he still reported to Steeler headquarters at Three Rivers Stadium from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. each day. And he frequently visited his farm and tracks. Around the office he was known as the Chief, the Prez, or the Old Man.

His wife of 51 years, the former Kathleen McNulty, died in November 1982 at the age of 78. He had 34 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren.

Rooney was born on Jan. 27, 1901, in Coultersville in South Versailles, the eldest of nine children born to Daniel and Margaret Rooney.

His father, a saloon keeper and brewery owner, moved the family to Pittsburgh's North Side when Art was 1 1/2 years old. Dan Rooney's saloon was located about 200 yards from Exposition Park, where the major-league baseball Pirates played before Forbes Field was built in 1909. The Rooneys lived above the saloon, on the site where Three Rivers Stadium now stands.

When he was 11, Rooney came close to drowning near the very site where his office would later be located. During one of the frequent floods that washed over the north shore in those days, Rooney, his brother Dan, and a boy named Squawker Mullen were paddling a canoe through the outfield at Exposition Park. Mullen upset the canoe. He and Dan swam to safety, but Art, who was wearing boots and a heavy coat, nearly drowned before reaching the grandstand of the old ballpark.

He never left his old neighborhood. Rooney lived all of his adult life in his old Victorian home on North Lincoln Avenue on the Northside, near his boyhood home and just a five-minute walk from Three Rivers Stadium.

He attended St. Peter's Parochial School on the North Side, and Duquesne University Prep School. Growing up, Rooney and his brother Dan were both well-known local athletes. Rooney attended Indiana University of Pennsylvania, which was then known as Indiana Normal School, for two years, graduating in 1920. The school yearbook describes him as "a young baseball player of great promise."

Rooney later attended Georgetown and Duquesne universities and Washington & Jefferson College.

He was twice offered a football scholarship to Notre Dame by Knute Rockne but did not accept.

By the mid-1920s, Rooney had been offered baseball contracts by the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox. He played for a while in the minors, and in 1925 was player-manager of the Wheeling team in the Mid-Atlantic League, but an arm injury ended his major-league hopes.

Rooney also boxed in the '20s. Besides winning the AAU welterweight crown, he was selected to the U.S. Olympic Boxing team in 1920, but declined to participate.

Rooney often won money facing traveling carnival fighters. Patrons were offered money if they could stay in the ring with the carnival's fighter for three rounds.

"Sometimes the problem was carrying them for three rounds," Rooney once said. "They couldn't fight. If they could fight, they wouldn't be in the carnival."

Rooney maintained his interest in boxing long afterward. In 1951, he promoted the heavyweight title fight in which Jersey Joe Walcott knocked out Ezzard Charles at Forbes Field.

Rooney never held a "regular" job in his life, except for a half day. He worked one morning in a steel mill, then quit. "I never even went back for my paycheck," he later recalled.

He was involved in several business enterprises. One of them was a pre-Prohibition partnership with Barney McGinley, whose son Jack, Art's brother-in-law, is now part owner and vice president of the Steelers. Together they owned the General Braddock Brewing Co., which made Rooney Beer.

Rooney also made one reluctant venture into politics in the mid-30s when the Republican Party persuaded him to run for Allegheny County register of wills. In his only speech, he said "I don't know anything about running the office, but if I win, I'll hire somebody who does." He was not elected, but his unique speech drew mention in Time Magazine.

It was sports, however, that received most of Rooney's entrepreneurial attention. He founded several semipro football teams, but the small amount of money they took in from passing the hat among the crowd at games went mostly to pay the players. Rooney sustained himself mainly through wagering on horses, for he is said to have been one of the greatest handicappers in that sport.

Through the lean financial years before television contracts and sellout crowds made pro football the lucrative business it is today, Rooney kept the Steelers solvent through his racetrack winnings.

Through the lean financial years before television contracts and sellout crowds made pro football the lucrative business it is today, Rooney kept the Steelers solvent through his racetrack winnings.Many believe that the $2,500 he used to buy the team came from his wagering, but he claimed he honestly couldn't remember if that was true.

What is true is that three years after buying the Steelers, Rooney made what might be the biggest killing in racing history. He never revealed the amount, but various reports place it anywhere between $200,000 and $358,000 Depression-era dollars. He hired a Brinks truck to bring his winnings home from New York, and when he got back, he emptied his pockets and told his wife, "We never have to worry about money again."

The story unfolded this way:

Rooney, who had first visited a race track at the age of 23 and was already a horse player of some renown by his mid-30s, attended a plumbers' union dinner in Harrisburg with two friends in August 1936. From there, they went to the Empire City race track the following day. That was before pari-mutuel machines adjusted odds, when bettors wagered with bookies on the grounds.

Starting with $20, Rooney won about $700 from a grandstand bookie.

"I felt sorry for the guy because it really clubbed him right off, so I went back to him to give him a chance to get even and I let the whole thing go. Well, I had three or four winners and ended up breaking the guy," said Rooney.

He left Empire City that Saturday having won about $21,000. Monday was opening day at Saratoga, so Rooney and his friends drove there. His first bet was an 8-1 shot named Quel Jeu. It was the first of five long-shots that he hit among other winners that afternoon.

"I came close to sweeping the card," he said. "It was the best day I've ever had."

Bill Corum, sports editor of the old New York World Telegram, was with Rooney on the trip and wrote about his winnings. Soon, other reporters trailed Rooney to the track.

Some proceeds from that spree went to an orphanage in China. Art's brother Dan, who became a Franciscan priest and eventually athletic director at St. Bonaventure, was a missionary in China then, and Art sent him a considerable amount when he got home from Saratoga.

Other stories of Rooney's generosity are legendary. He donated large sums to numerous charities. According to one story, a priest came and asked Rooney for money to help start a Catholic oprhanage. Rooney peeled off $10,000 and handed it to the priest, who asked, "Are these ill-gotten gains?"

"Why no, father, I won that money at the race track," Rooney said.

He always shied away from publicity for his benevolence, however, and quietly lent a helping hand to friends or to players with problems. He was a well-known soft touch for anyone with a hard-luck story, and often gave money to total strangers who wandered into his office with a sad tale.

Rooney always remained interested in racing, and attended the Kentucky Derby and Irish Derby every year. But he says he restricted his betting to racing, and never wagered on football or baseball.

Rooney's first football team was called the Majestics. Later they became Hope-Harvey, named for the Hope firehouse where the players dressed and for a physician named Harvey, who tended the players. Still later, Rooney's team was known as the J.P. Rooneys.

In 1933, a change in the Pennsylvania Blue Laws allowed professional sports to be played on Sunday, so Rooney bought into the NFL.

"I paid $2,500 for the franchise. If I held out, I probably could have gotten it for nothing," he said.

In those days, the NFL was a tenuous financial proposition. Only two clubs made money regularly, Green Bay and the Chicago Bears.

"In those days, nobody got wealthy in sports. You had two thrills. One came Sunday, trying to win the game. The next came Monday, trying to make the payroll," he often said.

Rooney's Pirates, as the club was known in the '30s, was a loser not only at the gate, but also on the field. It would be 10 seasons before the team would have a winning record, and 40 before it would win any title.

Years later, after his team had become a champion, an image of Rooney as the carefree loser emerged. He always claimed that was inaccurate.

"I didn't want to lose and I took losses as hard as anybody could take them. But I could take it," he said.

Rooney had a standing rule in his home that no member of the family was allowed to mention the Steelers for two days following a loss.

"That's how much it bothered me. I didn't want to read about it. I didn't want to see the films. I didn't want to have anybody tell me we gave it a good try," he said.

On the other hand, Rooney never denied that he had a good time as an owner in the early days of the NFL.

"I got a little upset about everyone always referring to those first 40 years as the bad years. Some of those 40 years were good. It was all fun. We traveled on a train or bus, and you got to know everybody. You got close with everybody."

Rooney's club had its share of characters, such as Coach Johnny Blood in 1935. Among his numerous other exploits, Blood once failed to show up for an exhibition game. But the Pirates also had some good athletes. In an era when most pro football players were paid $150 to $200 per game, Rooney stood the sports world on its ear in 1938 by paying "Whizzer" White, the All-American from Colorado, $15,800 a season.

In 1940, Rooney sold the Pirates and bought a half interest in the Philadelphia Eagles. He then engineered a switch whereby the two cities swapped franchises, putting Rooney back in Pittsburgh as part owner and vice president. The next year, the team changed its name to the Steelers.

When Rooney's partner, Bert Bell, became NFL commissioner in 1946, Rooney became president and controlling owner.

Because of the attendance and money problems, Rooney had offers to move the franchise to a half-dozen other cities, but he never did.

"I couldn't leave Pittsburgh. I wouldn't leave Pittsburgh. My home is here," he said.

The Steelers finally tied for first place in 1947 with the Philadelphia Eagles, but lost the Eastern Division title in a playoff. They also had a near-miss in 1963, needing only a victory over the New York Giants in the final game to win the division. But they lost that one, too.

Other than that, the Steelers were perennial losers.

It was Rooney who inadvertently gave his team its most notorious nickname of that era. In the late '40s, the Steelers got new uniforms. During training camp a sports writer was beside Rooney as they watched practice. The writer asked the Chief what he thought of the new outfits. "The only thing different is the uniforms. Inside, it's the same old Steelers," he said.

"Same Old Steelers," was a tag the club couldn't live down for another 25 years.

Rooney's son Dan hired Chuck Noll to be the head coach in 1969, and after a 1-13 initial season, Noll built the Steelers into a winner. The team's first postseason game was in 1972 at Three Rivers Stadium against the Oakland Raiders. It culminated in one of the NFL's most historic moments, the "Immaculate Reception" by Franco Harris, who caught a deflected pass for the winning touchdown in the game's final minute. Ironically, Rooney missed the play.

"I was going down to talk to the boys. I was in the elevator and when I got off I heard the yelling outside, but there was nobody in the dressing room," he said.

The following week, however, the Steelers' hopes for a Super Bowl were dashed, 21-17, by the Miami Dolphins. It was one of Rooney's most hopeless moments.

"I always felt we would win a championship someday, until that Miami game," he said. "That's the first time I ever really got to the place where I felt I might not see it happen. In fact, after that game I said to some of the fellows I loaf with, 'I'm getting old. I'm not gonna be around here much longer.'"

But two years later, Rooney saw his Steelers win the first of their four NFL titles with a 16-6 defeat of the Minnesota Vikings in Super Bowl IX.

The players voted to award the game ball to him.

First published on October 14, 2007 at 12:00 am

No comments:

Post a Comment