By Robert Dvorchak, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Mark Murphy/Post-Gazette

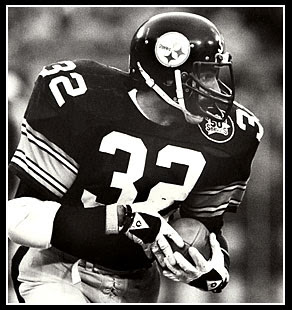

How Mike Webster is best remembered: In the middle of the line, taking on all comers, protecting his quarterback. The Iron Man played 15 seasons with the Steelers but ended his career with the Kansas City Chiefs.

Tunch Ilkin was a wide-eyed, middle -round draft pick at training camp in 1980, and like everyone in America with an interest in pro football, he was well aware of the stature of Pittsburgh's team.

"When I walked onto the campus at Saint Vincent's, it was as if I had walked into the Pro Football Hall of Fame," he said. "NFL Films had that highlight reel with John Facenda, the voice of the football gods, saying: 'There are 27 teams in the National Football League. And then there are the Pittsburgh Steelers.' "

About 20,000 fans had showed up to watch practice, a much bigger crowd than the 13,483 paying customers at the franchise's inaugural game in 1933. The slogan for the new decade focused on keeping the four-ring reign going, with none other than Joe Greene setting the goal as "One for the Thumb in '81."

The start was promising. The season opened with a win over Houston, which had loaded up with former Raiders in an effort to kick in the door after losing two straight AFC championships in Pittsburgh. But some uncharacteristic lapses and injuries to key players had the Steelers fighting for their playoff lives when they visited the Astrodome on a Thursday night for a rematch.

At the time, team president Dan Rooney was recovering in Mercy Hospital after suffering hip and knee injuries in an auto accident in late November. And for the first time in 40 games, the Steelers were underdogs.

A boisterous Houston crowd sang "Luv Ya Blue." And Oilers owner Bud Adams had hired a character named Krazy George who banged on his drum when the Steelers had the ball. The offense that had dominated the NFL had three interceptions, two lost fumbles and zero points in a 6-0 defeat. The curtain fell on the team that had made eight straight playoff appearances.

"You win as a team and you don't point fingers. Losers point fingers. And we are not losers," coach Chuck Noll said in the aftermath. "We have had difficulties in years past and have had the ability to overcome them. This year we didn't."

The Steelers were officially eliminated before their final game of the season, a Monday night loss to the San Diego Chargers.

"One of the things about being on top is that you will be falling, and that fall will be bad," Mel Blount said.

Joe Greene would have to wait a quarter of a century for his thumb ornament. But as always, he put the moment in perspective. "If this is the end of an era, I don't want it to be a funeral. We've had great moments. Special moments," he said.

Nothing lasts forever. Not even the Steel Curtain could stop Father Time. When the clock ran out on the season in San Diego, ABC showed some super highlights accompanied by "Winners" by Francis Albert Sinatra. The colonel in Franco's Italian Army sang with feeling but without the Pittsburgh accent:

Here's to the winners. Lift up the glasses.

Here's to the glory still to be...

Here's to all brothers. Here's to all people.

Here's to the winners all of us can be.

On to their 'life's work'

The afterglow of the '70s was evident when the Steelers marked their 50th anniversary in 1982. But at the time a banquet was held at the David L. Lawrence Convention Center on Oct. 9, the NFL season had been shut down by a labor dispute over distribution of revenue.

Count Basie performed. Pete Rozelle gave a special award to the Rooneys. An all-time team was honored. And Howard Cosell was the master of ceremonies.

"This is still the City of Champions. The cheering has stopped for now, but here, in Pittsburgh, the Renaissance City, the cheering will never stop," Mr. Cosell said. "When you play Pittsburgh, you play the whole city. Yes, it's still the City of Champions. It has nothing to do with victories. Pittsburgh has a winning character."

Familiar names announced retirements, or as Mr. Noll put, got on with their life's work. Not all of the exits were as graceful as they should have been.

Terry Bradshaw had high-profile marriages and breakups with a former Miss Teenage America and an international ice skating star. He dabbled in a TV pilot with country singer Mel Tillis and made movies with Burt Reynolds. But the end to his football career came when the elbow of his gifted right arm betrayed him.

Following surgery to repair a damaged tendon, the MVP of two Super Bowls sat out the first 14 games of 1983. He returned for one incredible curtain call, sparking the Steelers to a win over the New York Jets en route to the team's first division title since 1979.

At 35, he completed five of eight passes for 77 yards and two touchdowns in little over a quarter. Although the throw blew his elbow out for good, his last completion was a 10-yard strike to Calvin Sweeney. His last game boosted his career totals to 212 touchdowns against 210 interceptions. He watched from the sidelines at playoff time.

John Stallworth's 500th career catch came in a game played with replacement players during the 1987 season, his last.

Mike Webster also crossed the picket line to play in replacement games. The Iron Man set franchise records for longevity -- 15 seasons and 220 games, including 177 consecutively. But his last season was played in a red Kansas City helmet.

And then there was Franco Harris.

On the advice of agent Bert Beier, he held out in a contract dispute in 1984. The Steelers thought they had a deal, but the holdout continued. Finally, the Steelers released the man who caught the Immaculate Reception, was MVP of the first Super Bowl win and was just 353 yards shy of Jim Brown's all-time rushing record with the Cleveland Browns.

"We did everything possible to sign Franco," a distressed Dan Rooney said at the time. "By not reporting to camp, he placed us in a position where we had no alternatives left. It would not be fair to the team, the players and coaches to let this situation continue."

When asked about the holdout, Mr. Noll said: "Franco who? I don't know who he is."

Therein lies one timeline of the dynasty -- from the headline "Joe Who?" when Joe Greene was drafted to the unsentimental "Franco who?"

Mr. Harris played eight games with the Seattle Seahawks and gained 170 yards. He and the Steelers have long since patched things up.

Curtains come down

Tunch Ilkin followed a familiar path to Pittsburgh. A native of Istanbul, Turkey, he emigrated with his family when he was 2 and grew up in Chicago. After being drafted by the Steelers, he marveled at the ethnic diversity of his new home -- from the Croatian Club in McKeesport to the Slavic Club in Bethel Park.

"I thank God every day for coming here and playing for this organization. I wouldn't trade my experience for anything," said Mr. Ilkin, who has spent 27 years as a player and broadcaster with the Steelers. "But it was a blessing and a curse all at the same time. There was this blessing that I got a chance to learn from and play with the very best. But when they left, they cast a very long shadow."

Immigrants played a vital role in the Pittsburgh story. They came by the ship load, in third-class steerage, to work the mines and mills when the region was America's open hearth. The job were dirty and the conditions were dehumanizing, but they went to work to feed their families while producing the steel for the gates to the Panama Canal, the armor for the nation's battleships and the skeletons for skyscrapers and bridges.

Then the curtain came down on Pittsburgh's identity as the Steel City. By the time the decade was over, the steel industry had all but vanished. Companies went bankrupt. Mills were shuttered and dismantled. U.S. Steel acquired energy companies and changed its name to USX.

Left with no jobs and no opportunities, workers by the tens of thousands sought employment in other regions, leaving their extended families and their homes behind.

But wherever they went, they kept their ties. And the most visible connection was their loyalty to a football team, which resulted in a network of Steelers watering holes from Harold's Corral in Cave Creek, Ariz., to Mad Dog's in Hammock, Fla.

There was no Sinatra song to serenade the exodus from what became America's Most Livable City in 1984 and most "leaveable" city through a wrenching decade. But Charlie Daniels was onto something when he sang, on a 1980 album: "You just try to put your hand, on a Pittsburgh Steelers fan ... ."

Death of The Chief

Arthur Joseph Rooney, the son of Irish immigrants, became an American idol with the success of the Steelers. When he attended league meetings, executives from other teams pressed him on how he turned things around. He'd respond, through a haze of cigar smoke: "We're not doing anything different. Our players just got better."

He stayed true to his roots and never forgot those days in The Ward when he was a politician, sportsman, fighter and horse player.

The oldest son of a saloon-keeper, he prayed the rosary every day and went to Mass whenever he could, but he never professed to being a saint.

"I touched all the bases," he told his progeny.

Once, when a priest asked him if his $10,000 contribution for a new orphanage came from ill-gotten means, The Chief replied, "Why no, Father. I won that money at the racetrack."

He was tempered by the dark times when he walked home through the alleys so he wouldn't hear the critics tell him he was too dumb and too cheap to have a winning football team, an opinion he heard often in the first 40 years.

"I wasn't cheap," said The Chief, who was godfather to the first child of Billy Conn, the East Liberty fighter who once squandered his chance to beat Joe Louis for the heavyweight championship of the world. "Like Billy used to say, what's the use of being Irish if you can't be dumb."

His fellow NFL owners marveled at how he knew street urchins, porters, bellhops, waitresses, cooks, valets, cleaning ladies, grounds crew workers, cronies, lackeys, bishops, track owners, mayors, presidents and political heavyweights. He had the ultimate gift of a politician, making anyone he was talking to feel important.

The Chief passed away on Aug. 25, 1988, following a stroke. He was 87.

Fell on hard times

In any other decade, six winning seasons and four playoff appearances, including a berth in the AFC championship game, would have been cheered as wildly successful. But talk about a tough act to follow.

In 1984, the Steelers beat the 49ers in San Francisco. It was the only blemish on an 18-1 season that brought the 49ers another Super Bowl title. A rematch almost came to pass in that Super Bowl. But the Steelers lost the AFC title game to the Miami Dolphins and Dan Marino, the Pitt and Central Catholic star who was still available in 1983 when the Steelers drafted defensive lineman Gabe Rivera. Mr. Rivera was paralyzed in an auto accident in his rookie season and watched Terry Bradshaw's last game on TV from his wheelchair in the Harmarville Rehabilitation Center.

Louis Lipps

The Steelers drafted some top-notch talent during the decade, including Louis Lipps, Rod Woodson and Gary Anderson, the franchise kicker who was claimed off waivers. But they couldn't replace their Hall of Famers with the likes of Mark Malone, Keith Gary, Walter Abercrombie, Darryl Sims, John Reinstra, Aaron Jones and Tim Worley.

They were quarterbacked by Cliff Stoudt, who won two Super Bowl rings without ever getting his uniform dirty, along with David Woodley and Bubby Brister, who played minor league baseball under Jim Leyland and pro football under Chuck Noll.

Another quarterback was Steve Bono, who led the 1987 replacement team, and despite playing in just three games, is still listed on the Steelers' all-time roster along with teammates Joey Clinkscales, Spark Clark, Rock Richmond and Avon Riley. (In one replacement game at Atlanta, a fan held up a sign asking Mark Malone to stay on strike.)

Consecutive losing seasons in 1985-86 and the 11-loss season of 1988 prompted speculation that the Steelers could no longer keep up, even if they had only five losing seasons in the first 20 years at Three Rivers. But after opening the 1989 season with a 51-0 loss to the Browns at home and a 41-10 loss at Cincinnati, the Steelers regrouped to make the playoffs.

By that time, even the Iron Curtain had fallen.

Repopulating Canton, Ohio

With so many Steelers were being enshrined at the Pro Football Hall of Fame, a trip to Canton, Ohio, was an annual event. One memorable induction involved Jack Lambert, accompanied by Lambert's Lunatics who knew him as Jack Splat, Jack The Ripper, Count Dracula In Cleats, the man who once introduced himself on national TV as being from Buzzards Breath, Wyo., and the mean-tempered linebacker who said that instead of making up new rules to protect quarterbacks that they should play in skirts.

It has been said that Mr. Lambert, noted for his toothless snarl and leading the team in tackles in 10 of his 11 seasons, could have played in any era. His career was cut short by an injured toe, and his last game was the AFC title loss to the Dolphins.

On his retirement in 1985, he said: "There is not an owner or organization, a team or a coaching staff, or people in a city that I would rather play for in the entire world."

And when he was inducted into the Hall of Fame in the same class as Franco Harris, he bade goodbye.

"If I could start my life all over again," he said, "I would be a professional football player, and you damn well better believe I would be a Pittsburgh Steeler."

First published on October 14, 2007 at 12:00 am

Robert Dvorchak can be reached at bdvorchak@post-gazette.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment